Background

What are rental registries?

Rental registries are databases maintained by localities that contain information about rental properties and ownership. Depending on the registry’s design, rental property owners may be required to provide their name and contact information; details about the number, location, and types of units they lease; up-to-date rent levels and occupancy statistics; or other information. If the rental property owner must register in order to operate, the registry may also be known as a “rental licensing program.”

Registries provide both cities and residents with critical information. Without them, it can be difficult to determine who owns a rental property and how to contact owners, since landlords often create unique limited liability companies (LLCs) for each building they own to shield themselves from personal liability. This lack of transparency can prevent residents from learning about the landlords they rent from, or are considering renting from, creating a power imbalance. It also creates challenges for localities tasked with enforcing housing quality standards, rent regulations, and other rules, or trying to distribute services that can benefit tenants and landlords, such as rehab or rent payment assistance.

More broadly, there is a persistent scarcity of reliable data sources on rents and rental units. As a result, many cities struggle to understand their rental stock and track rent changes, which makes it difficult to design effective policies at both local and national levels. Registries can be a valuable tool in bridging this information gap.

Benefits and unintended consequences of rental registries

Housing quality

Cities often say they implement rental registration and licensing programs to make their inspection and housing code enforcement efforts more proactive. Research has demonstrated that complaint-based inspection programs do not adequately or equitably identify housing code violations. The first step in implementing a proactive inspection program is often creating a registry so that localities can accurately identify rental properties and who owns them. Some localities even make inspection a prerequisite for registration.

More proactive approaches to rental inspections have made a significant difference in housing code enforcement. For example, between the establishment of Los Angeles, CA’s Systematic Code Enforcement Program (SCEP) in 1998 and its evaluation in 2005, “more than 90 percent of the city’s multifamily housing stock [was] inspected and more than one and half million habitability violations [were] corrected. The result [was] an estimated $1.3 billion re-investment by owners in the city’s existing housing stock.” And between 2008 and 2013, Sacramento, CA’s Rental Housing Inspection Program (RHIP) estimated that it “reduced housing and dangerous building cases by 22 percent,” based on a declining share of code violations each year since the program’s inception. But even if they do not form the basis for a proactive inspection program, rental registries can help cities track down problem landlords and discourage absenteeism, as in the case of Buffalo, NY.

Rent regulations

Another common reason to create a rental registry is to enforce rent regulations. For instance, a report commissioned by the City of Los Angeles found that 27 percent of renters had rent increases that exceeded the allowable ceiling, and thirty-four percent of renters were incorrect about, or unaware of, the rent-stabilized status of their unit. As a result, the report recommended the city adopt a comprehensive rental registration system. Other cities have found success using registries to enforce rent rules, but their success has varied based on how actively they engage in activities such as monitoring and information dissemination. For example, in Berkeley, CA, a city with active enforcement and relatively high registration fees, at most five percent of tenants were paying a rent over the regulatory ceiling. In Newark, NJ, stepped-up outreach and enforcement of the rental registry helped increase the number of landlords registering under and complying with the city’s rent control ordinance – from 520 in 2018 to an all-time high of 2,885 in 2020 (an increase of 454 percent). A 2019 report for the City and County of San Francisco, CA, concluded that “active enforcement involving regular communication between rent programs and landlords and tenants results in a higher rate of compliance with program requirements than found in cities such as San Francisco and Oakland which are less active and charge lower registration fees.”

Data collection

Beyond enforcing housing quality and rent rules, rental registries have great value as data collection tools. Understanding rental ownership and rental property characteristics allows planners and policymakers to effectively target resources and implement policies to support small landlords and deliver rental assistance to both landlords and tenants. It may also help them identify households at risk of displacement due to rent hikes. There are many examples of housing policy research that has been made possible by rental registries: Kuhlmann et al. (2023) and de la Campa et al. (2021) on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on landlords; Garboden and Newman (2012) on preserving low-end rentals in Baltimore; and Preis (2023) on where landlords live in comparison to where their properties are located. Given the national need for better data on landlords and rental affordability, some researchers have even called for the federal government to develop a model rental registry and provide incentives for jurisdictions to adopt and enforce it.

Unintended consequences

The evidence for whether rental registries have unintended consequences for renters is mixed. A 2003 report for the City of Milwaukee examining rental licensing programs in fifteen cities warned that these programs’ fees and administrative costs could be passed on to renters, thereby decreasing affordability. Yet, officials in Minnesota cities with rental licensing programs believed that even if the costs of the license and fees were passed on to tenants in the form of rent increases, those increases would be nominal (no more than $10 per month). In Los Angeles, rent stabilization limits how much landlords can adjust rent to reflect new fees. Nevertheless, it’s worth noting that a 2009 survey of 2,036 rent-stabilized landlords in the city found that nearly 80 percent claimed not to pass either registration or inspection fees on to their tenants. Cities can also take preventative actions, such as reducing fees and identifying alternative funding sources to implement their registries. When cities link rental registries to rent control or stabilization ordinances, they can precisely regulate how much of the fee may be “passed through” in the form of a rent increase. Cities can also adopt a cooperative approach to enforcement, offering education and technical and financial assistance, which may reduce landlords’ need to raise rents.

Key features of rental registries

In the summer of 2023, the Lab conducted an internet-based search of local ordinances establishing rent registries and related documentation. We identified 46 registries and tracked their jurisdiction, date creation, overseeing department, stated purpose, coverage (meaning which rental properties are subject to the registry), participation, information collected, registration fees, penalties for noncompliance, and any available data on compliance rates and effectiveness. This scan allows us to understand the variation in registry design and determine which features are most widespread.

Figure 1. Rental Registries Included in the Scan, by City Population

Source: Housing Solutions Lab

Purpose

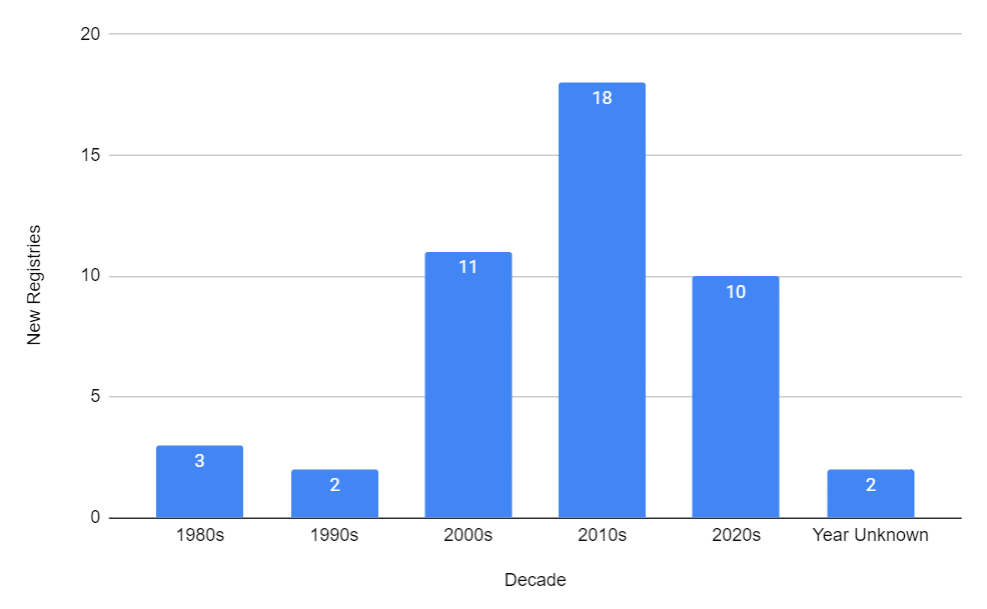

The oldest rental registries captured in our scan were established in the 1980s in Berkeley, Detroit, MI; and New York City (see Figure 2). Even these early registries demonstrate a variety of purposes. Berkeley created its registry in 1980 to allow the city to enforce a new law regulating rent increases and was the subject of heated debate among landlords, who argued (unsuccessfully) that the registry infringed on their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Detroit followed four years later with a registry focused on improving housing quality at a time when the city faced widespread disrepair and abandonment. The stated purpose of New York City’s 1988 registry was to allow the city to contact landlords in case of an emergency – or, more likely, a code violation.

Soaring rental costs in some cities and persistent issues with rental quality and abandonment in others formed the backdrop for the establishment of more registries in the following decades. Eleven of the registries in our scan were adopted in the 2000s, 18 in the 2010s, and 10 more after 2020. The most commonly stated purpose for these registries was housing quality and safety (this applies to 22 registries in our scan, or 48 percent). For example, cities say their registries help “prevent and correct conditions in residential rental units that…adversely affect the health, safety, and welfare of the public” (Renton, WA) and “identify problem properties and absentee landlords,” (Buffalo, NY). Other registries, like Berkeley’s, were created to enforce rent control laws. Six of the registries in our scan, or 13 percent, fall into this category; all are in California. A minority of registries stated their purpose as tracking evictions and protecting tenants (three registries, or 7 percent). Portland, OR’s registry “help[s] provide essential support for tenant protection policies.” Finally, some local governments cited contacting landlords as their primary purpose (five registries, or 11 percent). Skokie, IL’s registry, for instance, is designed to “strengthen the partnership between the Village and rental property owners.”

Figure 2. New Rental Registries in Scan by Decade

Source: Housing Solutions Lab

Coverage

Most registry ordinances (83 percent of those in our scan) require all non-owner-occupied rental units to be registered. Others are targeted based on the locality’s policy goals. For example, in Los Angeles, the rental registry is meant to help enforce the city’s Rent Stabilization Ordinance by collecting actual rent data, so it only applies to rent-stabilized units. Some rental registries focus on larger rental properties; in Houston, TX, and Fort Worth, TX, registration is mandatory for rental properties with three or more units. This may ease the burden of administering the registry but also excludes a significant share of the stock (nearly 23 percent of rental units in Houston are in one-to-two-family structures). Registries that specifically target housing quality may narrow their scope to properties exhibiting signs of unsafe conditions. In Austin, TX, the Repeat Offender Program registers rental properties that have received multiple code violations and designates them on a publicly accessible map.

Information gathered

Localities choose what information to collect with registration, and what balance to set between gathering enough detail to serve the registry’s purpose and creating an onerous process for owners. Based on our scan, rental registries gathered data in four general categories: contact information, property and unit characteristics, rent information, and tenant information. They usually collected these data via an online or physical questionnaire, although some registries asked landlords to submit additional documents such as an affirmation that the tenant received fair housing rights, proof of insurance, a lead paint safety certificate, or permits.

The most basic data that localities collected were rental property owners’ names and contact information; just over half of registries in our scan also collected contact information for the property manager. Some registries also gathered contact information for the property’s tenants or its insurance provider. Exactly who must register their contact information is important. For example, a report from the Urban Institute found that Philadelphia’s rental licensing program did not ask LLCs to register rental properties to individual owners, making it difficult to proactively inspect properties whose owners have a history of violating housing codes or hold them accountable.

Property characteristics included basic identifying details such as the property’s street address, parcel number, or real estate tax account number. Others included the number of units in a building (occupied and vacant), the year the building was constructed, and the number of parking spaces. These kinds of data could help a locality track vacancy, target lead paint remediation or rehab programs, and estimate the need for parking in case of future development. Specific details about units, such as the number of bedrooms or bathrooms and the square footage, can be useful in designing and targeting rental assistance programs or anticipating future housing needs.

Property and unit information is even more valuable combined with data about current rents, such as rent amounts, when and by how much the rent was last increased, services included in rent (such as parking and utilities), and security deposits. This information gives localities the power to accurately measure rental affordability and makes it possible to enforce protections against large or arbitrary rent increases.

To help cities enforce safe occupancy levels and track turnover rates, tenant information might include the number of tenants in a property or unit and lease start and end dates. Author Shane Philips argued in Shelterforce that rental registries should go even further by adopting “tenant registration,” allowing renters to verify or challenge their landlord’s claims about the rent and lease terms.

Frequency and fees

According to our analysis, most rental registry ordinances required landlords to register annually, although a few required registration only every few years during certificate of occupancy application or renewal or at the point of sale. A minority of registries were based on one-time registration, relying on landlords’ good faith to update their information as it changes.

As part of the registration process, property owners must typically pay a fee per property or per unit, on a one-time or re-registration basis. In our scan, roughly half of registries levied a per-unit fee, most commonly between $15 and $50 per unit. The lowest per-unit fee we identified was in Concord, CA, where the registration fee is $5.25 per unit per year. The highest was in Oakland, at $101 per unit per year. Registration may also be tied to an inspection, which can incur its own fees. About half of registries in our scan required inspections as part of the registration process, and inspection fees typically ranged between $50 and $100 per unit.

Penalties

Most localities placed a fine on landlords who failed to register. In our scan, these fines ranged from $25 per day in College Station, TX, to $500 per day (after the first 10 days of noncompliance) in Seattle, WA, to a maximum of $5,000 in Oakland. Other enforcement mechanisms included prohibitions on raising rent, leasing vacant units, or filing for eviction; the local government taking possession of the noncompliant property; or, in rare cases, imprisonment, as in Maplewood, NJ. On the other hand, some localities offered incentives, such as allowing only registered landlords to apply for rental assistance or other public programs, or hired landlord liaisons to encourage registration.

Enforcement and compliance

The benefits of rental registries – which include the ability to contact landlords, enforce housing quality and rent regulations, and track trends in the rental market – are only achieved when a significant portion of properties comply. But compliance is difficult to measure, since it is hard to assess the percentage of rental properties registered without a sense of the rental stock as a whole – precisely what the registry itself is meant to quantify. Existing evidence suggests that compliance varies widely across jurisdictions. For instance, Elijah de la Campa and Vincent Reina found in a 2022 study of ten cities that compliance with rental registries ran the gamut from “around 10 percent in Indianapolis, to upwards of 70 percent in Trenton, to nearly 95 percent for San Jose’s more limited registry.” The research also suggests that rental property size plays an important role in compliance. A study by the Pew Research Center found that smaller rental properties are much less likely to be registered in both New York and Cleveland. Likewise, a 2013 NYU Furman Center analysis found “virtually no compliance among one- and two-unit buildings that are required to register” in New York City, but saw compliance reach 85 percent among 50-plus-unit buildings. Study authors noted that owners of small rental properties may have less capacity for rental registration, may be less connected to government systems and therefore less aware of the ordinance or how to comply, or may be motivated to avoid registering if their properties are in poor condition.

Another important factor in boosting compliance is robust enforcement. Our scan suggests that various municipal agencies manage rental registries across the country, including housing departments, county assessors, community development offices, and building inspectors. Some cities created entirely new licensing and registration offices to manage their registries. Regardless of where it is housed, implementing a rental registry requires staff capacity for landlord outreach, processing applications, IT management, and audits and inspections – and comes with significant administrative costs. For instance, San Francisco estimated in 2019 that creating a registry only for its rent-stabilized units would entail a start-up cost of $300,000 and annual costs of between $1.7 million and $3.6 million. The large range is dependent on whether the city decides to adopt a more passive or active approach to enforcement. Meanwhile, Oakland calculated in 2022 that setting up a registry would come with an initial cost of $325,000. Additionally, the annual operational costs of running the registry would be around $789,000, with a major portion of the cost going towards staffing expenses. Cities typically aim to cover most or all of their operation costs with the revenue generated from fees but they may need to make significant trade-offs (such as exempting single-family rentals from registration) to do so.

Strategies for increasing compliance

Additional research points to ways to increase a city’s compliance rate. Research from Newark’s Office of Rent Control and the Behavioral Insights Team of the What Works Cities Economic Mobility Initiative found that sending landlords a “behaviorally informed mailer” – a carefully designed letter that encouraged owners to register (and cited a clear deadline and consequences for failing to meet it) – increased their likelihood of registering by more than 20 times and resulted in the registration of over 1,900 properties in two months. Another strategy might be to increase the penalties or incentives for rental registration, for example, by prohibiting unregistered landlords from filing for eviction. A guide on rental licensing prepared by Alan Mallach at the Center for Community Progress recommends tactics such as mass mailing and creating a citizen reporting system by which residents can see whether their rental is listed in the database, and, if not, can submit an anonymous report. Finally, sharing data across city agencies can help identify unregistered rental units. By linking data on housing complaints, inspections, code violations, and permits with their rental registry in a database called NEOCANDO, researchers at Case Western University in Cleveland were able to identify properties that are likely to be rentals and help the city target campaigns for registration and housing code enforcement.

Conclusion

Rental registries can be useful tools for local governments to enforce housing quality standards and rent regulations and collect important information about their rental stock. However, registries are of limited value if landlord compliance is low. Municipalities must carefully consider their goals in implementing a registry, what information to collect and how often, what fees and penalties to set, and how to promote landlord awareness and enrollment.

Examples

Alameda, CA, requires that landlords register each rental unit, including units that qualify as rent-regulated (multi-unit properties built before 1995), partially regulated (single-family homes, condos/townhouses, and multi-unit properties built after 1995), and some federally subsidized units. The program’s goal is to maintain a database of rental properties, including information about tenants and accurate rents collected by landlords so that the city can enforce rent control laws. If landlords do not register a unit for a fully regulated rental property, they will not be eligible to increase the unit’s rent.

Minneapolis, MN, passed a rental registry ordinance in 1991 requiring all non-owner-occupied rental properties to be licensed. The registry’s goal is to allow for increased communication and transparency between the city, landlords and tenants, and targeted outreach to support small landlords. The city uses a tiered fee structure based on the number of units and the property’s condition over the previous two years and offers workshops to educate landlords, which can help lower fees. The city has achieved over 90 percent compliance and maintains an open data portal and map of registrants.

San Marcos, TX, established a rental registry in 2018 with the goal of increasing communication between the city, landlords, and tenants – specifically to address housing concerns more proactively and to share information that could support tenants facing difficulties with paying rent and/or utilities. The city requires annual registration but does not require a fee.

Related resources

- Rental Registries. This PolicyLink article includes a working definition and some examples of rental registries.

- Raising the Bar: Linking Landlord Incentives and Regulation through Rental Licensing. Produced by the Center for Community Progress, this document is a practical guide to rental licensing programs.

- Are You Registered? An Analysis of Buffalo’s Rental Registry Code. This 2009 brief from the Partnership for the Public Good, a nonprofit think tank in Buffalo, discusses the goals, structure, and early outcomes of the city’s new registry ordinance.

- Review of the City of East Palo Alto Rent Stabilization Program. A report for the city’s rent stabilization board includes recommendations for how to structure and fund a rental registry.

Authors: Claudia Aiken, Jess Wunsch, Nora Carrier, Shira Kogan, Jerrell Gray, Will Viederman

Publication date: January 2024