A public housing property managed by Inlivian in Charlotte, North Carolina. Image credit: INLIVIAN.

A relatively small subset of PHAs, known as Moving-to-Work (MTW) agencies, currently have the authority to impose time limits or work requirements on assistance, but only a few have experimented with doing so.

Recent proposals aim to change this paradigm. President Trump’s “skinny” budget proposal for fiscal year 2026, sent to Congress on May 2, 2025, would replace HUD rental assistance programs with a state-administered block grant and would “newly institute a two-year cap on rental assistance for able-bodied adults.” On May 16, HUD Secretary Scott Turner and three other cabinet leaders authored a New York Times op-ed calling on Congress to enact work requirements across a swath of welfare programs, including federal housing assistance. In June, NPR reported that HUD was drafting a rule that would impose work requirements and time limits on work-able adults, or working-age adults who are not disabled.

This brief explores what we know about work requirements and time limits in the context of housing assistance. We divide the inquiry into two parts:

- First, we investigate the experiences of PHAs that have adopted these policies in the past and review relevant literature on their effectiveness in other safety net programs.

- The second part of this brief draws on ongoing research using HUD administrative data to understand who would be affected by work requirements and time limits if they were newly implemented across federal housing assistance programs.

Part 1: Learning from past experience

The first part of this brief focuses on the experience of PHAs that have adopted work requirements or time limits and reviews research about the effectiveness of such constraints in the context of other social safety net programs. This includes a scan of MTW agencies’ work and time limit policies, as well as a discussion held at a session of our PHA Community of Practice devoted to this topic. We also reviewed two reports commissioned by HUD in 2007 and 2022 and other published studies about the impacts of work requirements and time limits in housing and other social welfare programs.

Summary of key findings

We found relatively few examples of PHAs that have experimented with either work requirements or time limits, and considerable variation in how those that did structured and implemented these policies. Perhaps not surprisingly, given how rarely PHAs have adopted work requirements and time limits, we found just two rigorous evaluations of their effectiveness: one causal evaluation of the impact of work requirements on household outcomes and one study directly comparing housing programs with and without time limits. Nevertheless, our review surfaced useful insights and open questions about PHAs’ experiences with these policies, their effectiveness, and agencies’ capacity to implement them.

PHAs generally reported high compliance with work requirements and few evictions due to noncompliance; however, they also reported that participants made limited progress toward their economic self-sufficiency goals. Wages among working households were too low or volatile to support successful exits from assistance. One study found that work requirements paired with supportive services modestly increased employment rates for Charlotte, North Carolina, public housing residents. However, at least seven of 16 PHAs that we identified as adopting work requirements later changed or discontinued work requirements because they were deemed punitive or hard to administer. PHAs found that “noncompliant” households faced significant barriers to work.

Similarly, 11 of 17 PHAs that fully implemented time limits later removed them, either due to low uptake of time-limited programs, lack of capacity to administer or enforce them, or after determining that households reaching the end of their assistance periods still faced poverty, high rent burdens, and a high risk of housing instability. Some PHAs continue to implement time limits, and two have recently proposed new time limit policies to HUD. They believe that these measures can encourage participants to be more self-sufficient, shorten wait times for scarce housing assistance, and serve a greater number of households. However, it is challenging to design and implement time limits in a way that supports economic mobility and gives PHAs confidence they are not discharging households only for them to again face unsustainable rent burdens and housing instability.

Our review suggests that widespread adoption of work requirements or time limits would require clear guidance for PHAs, technical assistance to support policy design and effective implementation, and rigorous monitoring and evaluation to understand impacts on participants and agencies. A key challenge will be targeting these policies, minimizing administrative errors, and crafting hardship exemptions to ensure that households are not penalized for circumstances beyond their control, such as medical emergencies or business closures.

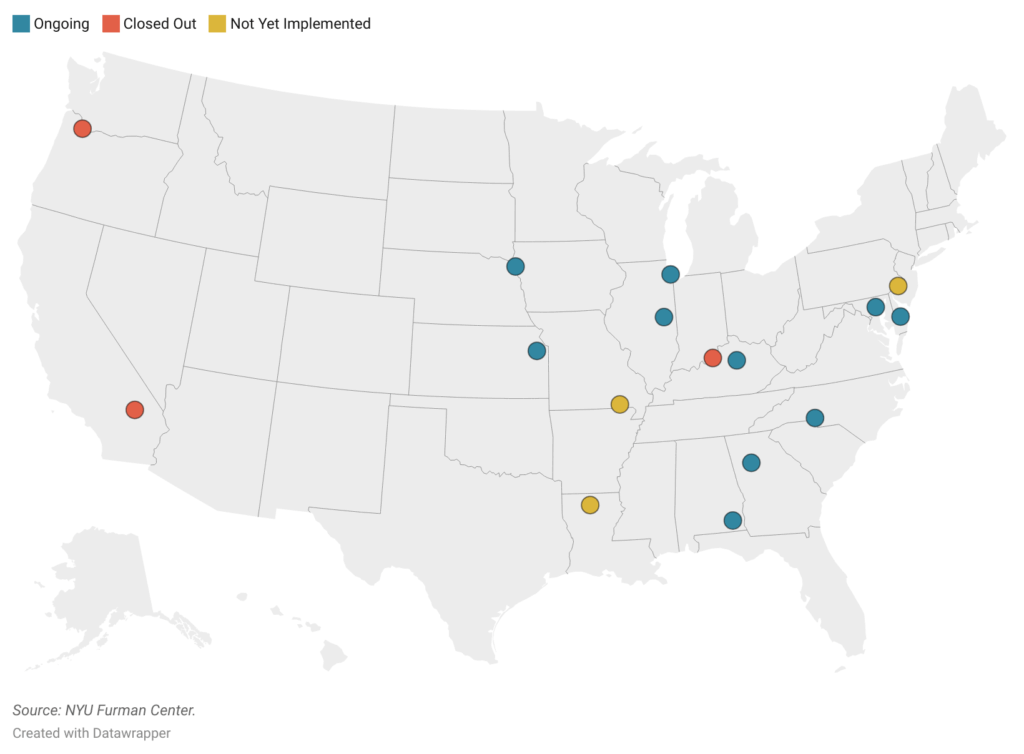

Work requirements

Our scan identified 16 housing authorities out of 139 MTW agencies and more than 3,000 PHAs nationwide that have either implemented or proposed work requirements at some point since the first MTW cohort launched in 1996. This list is unlikely to be exhaustive because while HUD requires MTW plans to list all approved activities regardless of whether they have been implemented, paused, or ended, the details provided can vary significantly. Most of the 16 agencies identified still have work requirements in place (see Figure 1, below).

Many of the PHAs that have experimented with work requirements are relatively small, while others implemented work requirements only for certain groups, such as households leasing up in newer single-family homes. The exceptions are Atlanta Housing Authority, INLIVIAN (formerly Charlotte Housing Authority), and Chicago Housing Authority, all of which have work requirements in force that apply broadly across their sizable voucher or public housing populations.

The policies captured in our scan typically applied to work-able adults, with discretionary exemptions available for residents experiencing medical emergencies, acting as sole caregivers to elderly relatives or sick or disabled children, or encountering other extenuating circumstances.[1] Usually, residents needed to apply for these hardship exemptions, for example, by presenting a doctor’s note. Only a few PHAs made automatic accommodations, such as by exempting one work-able adult in all households with children younger than 6.

Work requirement policies varied in terms of the minimum level of employment expected. While many agencies mandated only 15-20 hours of work per week, some required 25 or more, and one agency required that either the household head or co-head attain full-time employment.[2] Often, education and job training could count towards these minimums, and in some cases, volunteering was also considered acceptable.

Figure 1. Public Housing Agencies With Work Requirements

View the data in this spreadsheet.

PHAs often paired their requirements with services such as case management and career and financial literacy counseling. Some implemented them as part of a package of policies including time limits, flat rental subsidies, financial incentives, and credit-building and savings supports designed to help work-able households increase their income and achieve greater independence. Most agencies also provided a series of warnings and case management interventions before considering eviction or subsidy termination for households noncompliant with work requirements.[3]

Despite limited adoption, the experience of these PHAs offers valuable lessons about the impact of work requirements in federal housing assistance. A HUD-commissioned 2022 report examining the experience of nine PHAs implementing work requirements found that compliance was generally high and termination due to noncompliance was exceedingly rare. Agencies have also reported challenges, however. They found that households faced numerous barriers to employment, including lack of affordable transportation and childcare, past criminal convictions, fear of losing other welfare benefits, and the volatility that characterizes low-wage job sectors. In 2019, Atlanta Housing Authority reduced its work requirement from 30+ hours to 20+ hours per week because it “realized that most of its assisted households were being ‘penalized’ for working jobs in which employers would not schedule their employees for 30 or more hours to avoid triggering to the requirement to provide insurance under the Affordable Care Act,” according to the report.

Enforcing work requirements also requires significant staff time and capacity, especially when these requirements are tiered, have numerous hardship exemptions, or are paired with case management and other supportive services. At least four PHAs changed their work requirements to make them less administratively complex; for instance, in 2018, INLIVIAN replaced its two-phased work requirement with a single threshold of 20 hours per week for all work-able adults. Three other agencies ultimately discontinued their policies. One executive director attending our PHA Community of Practice noted that their agency had ended its work requirement because “we lacked the capacity to fully implement, track, monitor, support, and enforce” it.

Evidence from the literature

There is very limited rigorous evidence about the effectiveness of work requirements in the context of housing assistance. The only causal study, dating back to 2016, measured the impact of INLIVIAN’s work requirement on employment and hours worked among public housing residents in Charlotte. The researchers found that the policy did result in a modest increase in employment. Approximately one year after its imposition, unemployment among residents in two public housing sites receiving case management and supportive services decreased by 13 percent. In three other sites that did not receive these services, unemployment decreased by 11 percent. Meanwhile, in the comparison group, unemployment went up by five percent. The researchers also surveyed and interviewed residents, finding that a large majority thought the work requirement was fair, but also called for flexibility.

A non-causal study focusing on Chicago’s public housing residents also shed some light on what we might expect work requirements to achieve. Researchers calculated that of the more than 5,000 residents subject to work requirements in 2017, about half met the requirement, another 30 percent qualified for an exemption, and the remaining 20 percent were noncompliant. Among the non-working residents, most had no wage income at all. Yet no one knew of any instances of eviction due to noncompliance. Staff viewed the work requirement as a means of promoting residents’ self-sufficiency, but did not anticipate that it would result in substantial enough earnings increases to enable them to exit housing assistance. They also reported that lack of childcare, especially during job searches, along with mental health needs, presented major barriers to employment.

The slim evidence available about work requirements’ effectiveness in housing assistance is balanced by a great deal of evidence about their impact in other welfare programs. In the case of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps, work requirements dramatically reduce program participation without actually increasing employment or earnings.[4] Researchers hypothesized that “for a population that overwhelmingly has no income, whether earned or unearned, work requirements…will not be effective, as they do not address more pressing underlying barriers to work.”

The evidence from Medicaid is perhaps even more stark. When Arkansas attached work requirements to Medicaid for 10 months before a judge disallowed it, researchers found that many adults lost insurance, were unable to transition to other coverage, and that there was no increase in employment or hours worked.[5] Among a sample of Arkansans who lost their insurance, half reported having trouble paying medical debt, and more than half delayed taking medication or seeking medical care two years later. This loss was especially troubling, as the vast majority of people subject to the requirement were already working or should have qualified for an exemption, suggesting that the extra burden of proving compliance prevented eligible residents from accessing insurance.

The longest-term evidence about work requirements stems from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.[6] Researchers tracking Illinois families who received TANF in 1998 found that families faced with penalties for failing to meet work requirements, such as having their assistance reduced by half or suspended, were 44 percent less likely to be employed, after controlling for previous work experience and other factors. The threat of sanctions did not promote formal employment, either. Studies suggest that this is because those who are sanctioned are not those who refuse to work, but rather those who face the greatest barriers to doing so. Having less than a high school education significantly predicts a TANF sanction, as does being Black, likely because of differential treatment both in the labor market and in the welfare office. Many parents may also be sanctioned in error. In Tennessee, a third of sanction determinations in 1999 were ultimately not carried out because external review found that the family had come into compliance (70 percent) or the sanction should not have been imposed in the first place (30 percent). Finally, while TANF sanctions did not increase employment, they did result in a host of negative outcomes, including increased utility shutoffs, families selling their food stamps, and a higher likelihood of food insecurity and hospitalization among toddlers and infants.

Time limits

Our scan identified 19 housing authorities that have experimented with placing time limits on housing assistance. About a quarter of these have also tried or proposed work requirements. The time limits range from three to seven years, with the most common policy being a five-year cap on assistance, with the possibility of one two-year extension. Limits have usually been restricted to households with non-elderly, non-disabled adults. While a few applied broadly across a PHA’s voucher or public housing population, many were targeted to households referred by partner agencies or those opting into special programs designed to increase their income and independence.

As Figure 2 shows, 11 of the 19 agencies we identified as adopting time limits have ended their policies. Five of them did so before the first households subject to the time limit would have exited assistance. In one case, an agency cited a lack of interest; the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Housing Authority proposed ending its time-limited voucher pilot when participation shrank from 25 to 12 households in 2023, and existing participants struggled to attain self-sufficiency after the pandemic. The Louisville Metropolitan Housing Authority ended its five-year time limit on assistance for new single-family scattered-site public housing units in an attempt to increase occupancy in those units. Another frequently cited reason is the state of the economy, including a lack of well-paying jobs and skyrocketing rents. Still other PHAs pointed to the loss of a key program partner or their own lack of capacity to provide supportive services and monitor households’ progress in a way that would justify a time limit.

In at least one case, a housing authority terminated its time limits because they were associated with adverse outcomes. The Tacoma Housing Authority, in Washington, ended its time-limited, flat subsidy Housing Opportunity Program (HOP) based on an internal assessment that found households given HOP vouchers were less likely to successfully lease housing, experienced smaller increases in income, saw more negative exits (such as evictions), and faced higher rent burdens compared to those receiving traditional vouchers. The assessment noted that, for HOP households, “achieving self-sufficiency [i.e., achieving a household income that is 80 percent or more of the area median] appears to be as common as eviction or death.”

Figure 2. Public Housing Agencies With Time-Limited Programs

View the data in this spreadsheet.

Nevertheless, some time-limited programs appear to have stood the test of time. Two California PHAs, the Housing Authority of the County of San Mateo and Tulare County Housing Authority, have had time limits since 1999. In San Mateo, all new voucher households with work-able adults enter the agency’s “MTW Self-Sufficiency Program,” which provides mentorship and financial incentives but imposes a five-year time limit on assistance. In Tulare County, flat subsidies are paired with a five-year time limit for non-elderly or disabled families, without additional services designed to increase self-sufficiency. The then-executive director of the Tulare County Housing Authority argued in a 2005 op-ed for the Public Housing Authorities Directors Association (PHADA) that time limits were reasonable in Tulare’s relatively affordable housing market.

Another wave of PHAs whose time limits are still in place adopted those policies in 2012-2013 and have only recently begun to see households time out of assistance, in part due to extensions granted during the COVID-19 pandemic. They include the Delaware State Housing Authority; Elm City Communities/Housing Authority of New Haven, Connecticut; and the Housing Authority of the County of San Bernardino, CA. Researchers at Loma Linda University evaluating San Bernardino’s Term-Limited Lease Assistance Program, which included a work requirement component until 2019, found that participating families showed some early indicators of progress, including increases in employment, earned income (though declines in welfare income canceled these out), and access to health insurance. San Bernardino staff report that these households are nevertheless exiting the program below the poverty line.

Evidence from the literature

Much of the evidence about time-limited housing assistance comes from programs that serve people who are currently or have recently been homeless. Some of these programs have been shown to improve household outcomes. For example, rapid rehousing services reduced the likelihood of future spells of homelessness for single adults in Los Angeles. In Washington State, similar short-term assistance increased the odds of employment. Short-term housing cost subsidies paired with case management also helped housing-insecure families with children find and maintain stable housing in the Seattle area. Yet the Family Options Study, which directly compared long-term subsidies, such as vouchers, to short-term interventions like rapid rehousing and other homelessness services, suggested that long-term subsidies are more effective in reducing homelessness and overcrowding, though they may also result in lower rates of employment and earnings.

It is not clear whether or how these findings can be extrapolated to non-homeless families. The effectiveness of time-limited assistance for individual households is also likely to depend on various factors, including the local housing and labor market, the provision of supplemental services, and household characteristics. But the question of efficacy extends beyond the individual household to how many households can be served. The current system of generous, time-unlimited federal rental assistance serves only a small fraction of the households in need. Some researchers posit that “absent large infusions of additional resources into [existing] housing programs…there would seem to be value in exploring the impact of modest, time-limited subsidies to serve more people.”

Applying time limits to the existing public housing and voucher programs is likely to come with important trade-offs. A key question is whom to target for time limits, and whom to exempt. Existing research shows that a shrinking share of HUD-assisted households are headed by work-able adults; they are increasingly outnumbered by those with fixed incomes, including seniors and people with disabilities. If PHAs impose time limits only on work-able households, the composition of households served is likely to shift even more towards older and disabled adults over time. As noted below, many households with work-able adults also include children. Without exemptions for parents, fewer subsidy dollars may go towards children, who stand to benefit the most from the greater access to housing stability and better neighborhood environments that assistance may provide.

A second decision point is how long the term of time-limited assistance should be. As rents rise and incomes stagnate, even work-able households have been staying in federal housing programs longer. Depending on the duration of the assistance, time limits risk leaving families severely rent-burdened, especially in high-cost markets. Time-limited subsidies could also make it even harder for voucher holders to secure housing in the first place; more than 40 percent fail to do so as it is. Low lease-up rates could add to the administrative costs that time limits create for PHAs. As the former executive director of Tulare County Housing Authority observed, “it can’t be denied that we have experienced more work since we started timing out families. It takes time to move out families and place them in an expeditious manner without incurring large vacancy losses in public housing, and suffering reductions in administrative fees in the voucher program.”

Thirdly, PHAs must decide how much flexibility to build into their policies. Will they allow for extensions? Might they permit households to continue receiving a smaller subsidy for a certain period of time, for example? And under what circumstances might this flexibility be granted? These decisions will have significant consequences, both for households and for the agencies responsible for administering time limits; however, there is little evidence available to inform decision-making directly.

Part 2: Who would be affected by work requirements and time limits in housing assistance programs?

This second section of the brief reports on ongoing research using HUD administrative data to analyze which assisted households would be affected by new work requirements and time limits policies nationwide.

Summary of key findings

We found that nearly half of all assisted households are work-able and would therefore be subject to proposed work requirements and time limits. Roughly 40 percent of those work-able households (or one fifth of all assisted households) do not have wage earnings and could be at risk of losing their subsidy if work requirements were imposed and they were not able to secure employment that met requirements. Approximately 70 percent of those work-able households have been receiving assistance for longer than two years and would lose their subsidy if a two-year time limit was imposed on current households. Approximately two-thirds of households with work-able adults also include children.

Methods

We used detailed administrative data from HUD to identify which currently assisted households across the country would be affected by the proposed work requirements and time limits. We break out our analysis into two groups of households: Section 8 recipients and public housing residents. The Section 8 category includes the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program (tenant-based subsidies) and the Project Based Voucher (PBV) and Project Based Rental Assistance (PBRA) programs (project-based subsidies). We focus on households who were assisted in 2024, which is the most recent year of data available, but also analyze trends over time using past years of data.

Work requirement policies typically apply to working-age adults who are non-disabled (work-able adults). Time limits for other assistance programs have also generally applied only to households with work-able adults. The administrative data allowed us to identify the age and disability status of the household head as well as any co-head and/or spouse. We could also determine the ages of all other members of the household, though not their disability status. We categorized households as work-able, not work-able, or having unclear status using the following criteria:

- Work-able: The household head, co-head, or spouse was aged 18-61 and not disabled or there were other adults aged 18-61 in the household and the household earned wage income (suggesting at least one of these other adult members was work-able).

- Not work-able: There were no non-disabled adults in the household aged 18-61.

- Unclear status: The household head, co-head, or spouse was not work-able, but there were other adults aged 18-61 in the household and no wage income.

For this analysis, we designated a household as having wage income if there was earned wage income in the year 2024. Further analysis can explore how many assisted households had wage income in some years but not others, or had incomes above certain thresholds.

Who would be affected by work requirements?

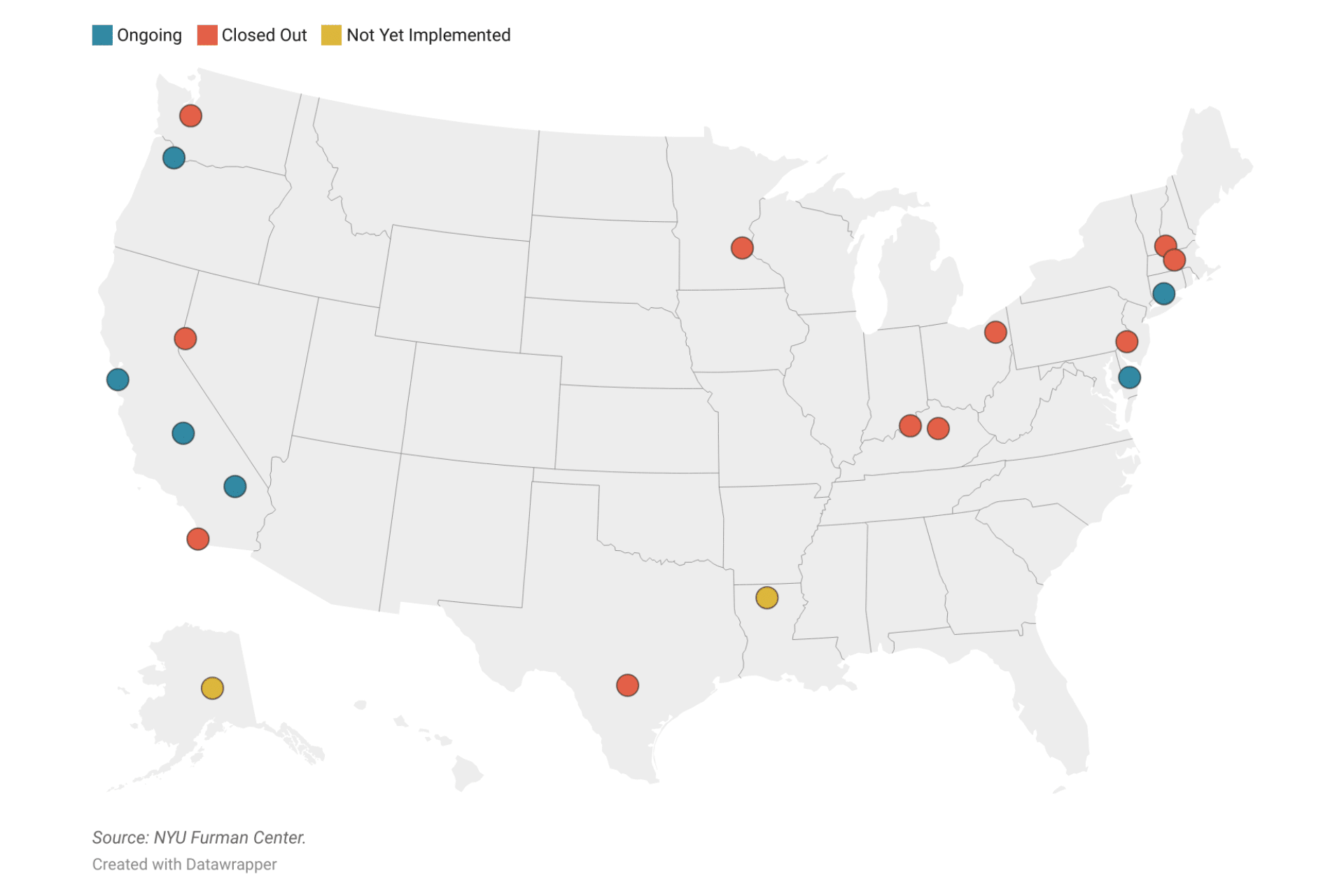

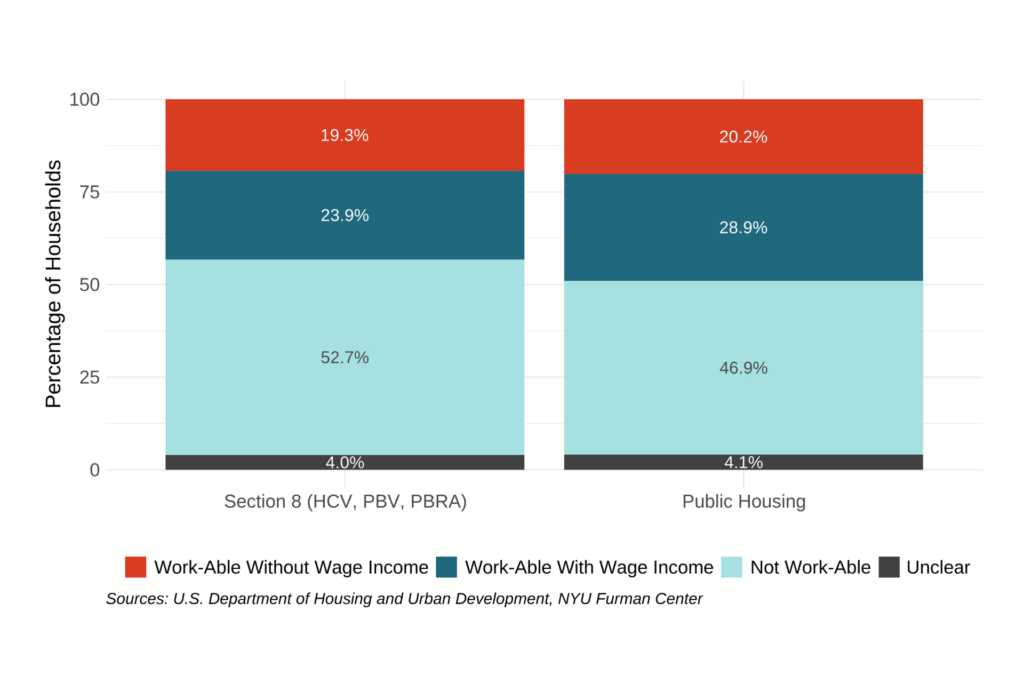

Forty-three percent of Section 8 households and 49 percent of public housing households were work-able in 2024 (see Figure 3). Approximately two-thirds of work-able households across programs were families with children. The share of households who are work-able has declined by roughly five percentage points in the last decade.

Figure 3. Households by Work-Able Status, 2024

View the data in this spreadsheet

Over half of work-able households earned wage income in 2024 (see Figure 4), suggesting many work-able households would already be in compliance with newly imposed work requirements. Work-able households who receive welfare such as TANF are also likely already subject to work requirements associated with these programs. However, it is possible that some work-able adults in the household may not be employed or that the new requirements could demand more hours or months of work than what each working adult currently puts in. These already working households would also be required to start reporting their work hours to the PHA, and some households may risk losing their assistance simply due to reporting burdens or errors in this administrative process.

Work requirements would also newly affect work-able households who do not currently earn wage income. In 2024, approximately one-fifth of households in each program included work-able adults but did not have wage income (see Figure 4). These households would be at risk of losing their subsidy if their work-able adults did not find new employment that met work requirements. In 2024, this totaled approximately 777,000 Section 8 households and 172,600 public housing households.

Figure 4. Households by Work-Able Status and Wage Income, 2024

View the data in this spreadsheet

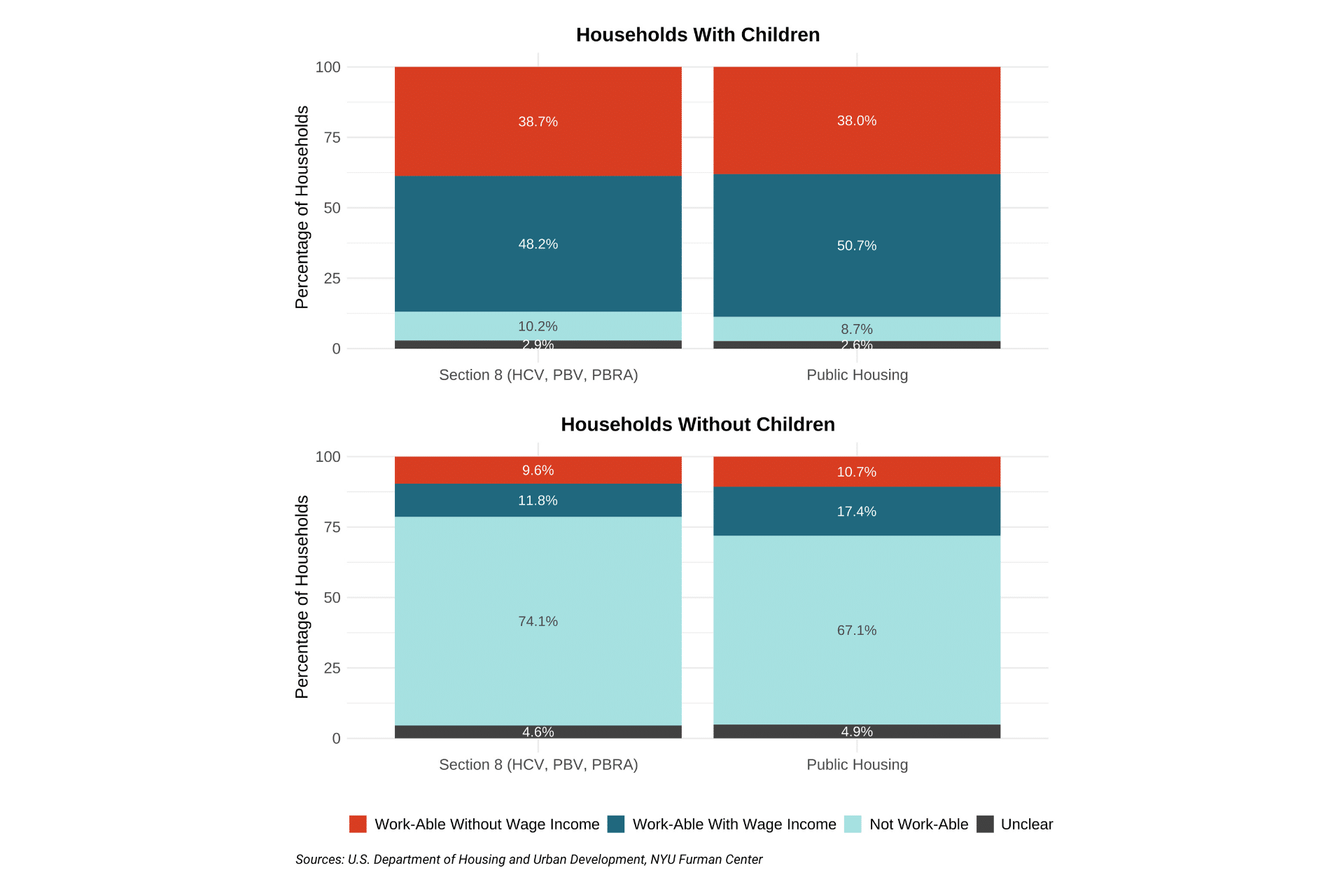

The share of households with work-able adults without wage income is considerably higher for households with children compared to households without children. Nearly 90 percent of households with children contain work-able adults. In 2024, about 38 percent of households with children across programs included work-able adults but did not have wage income and would therefore be affected by new work requirements (see Figure 5). This is a total of approximately 519,000 Section 8 households and 112,000 public housing households, or about two thirds of the potentially affected households. Most households without children are elderly or disabled households who are not work-able.

Figure 5. Households by Work-Able Status, Wage Income, and Presence of Children, 2024

View the data in this spreadsheet

Who would be affected by time limits?

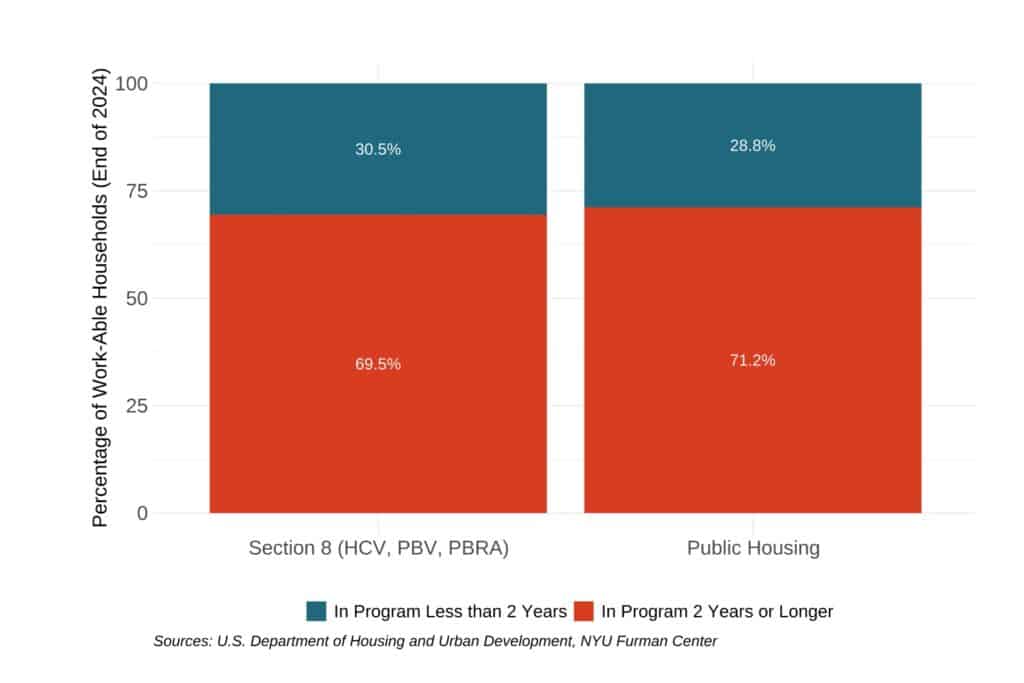

Time limits would likely apply only to work-able households, and the share of households who would be affected by new time limits would vary depending on whether the time limit is set to two years, as in current policy proposals, or if it is extended to a longer duration.

To understand which households would be affected by a two-year time limit, we first examined the proportion of work-able households still assisted at the end of 2024 who had received assistance for longer than two years. Of work-able households who were assisted at the end of 2024, 69 percent of Section 8 households and 71 percent of public housing households had been in the program for longer than two years (see Figure 6). This totals approximately 1,129,800 Section 8 households and 265,700 public housing households. If households currently receiving assistance are subject to a two-year limit, it would create significant disruptions and large administrative costs for PHAs who would have to evict all of these households and identify new ones to take their place.

Figure 6. Time in Program for Work-Able Households, End of 2024

View the data in this spreadsheet

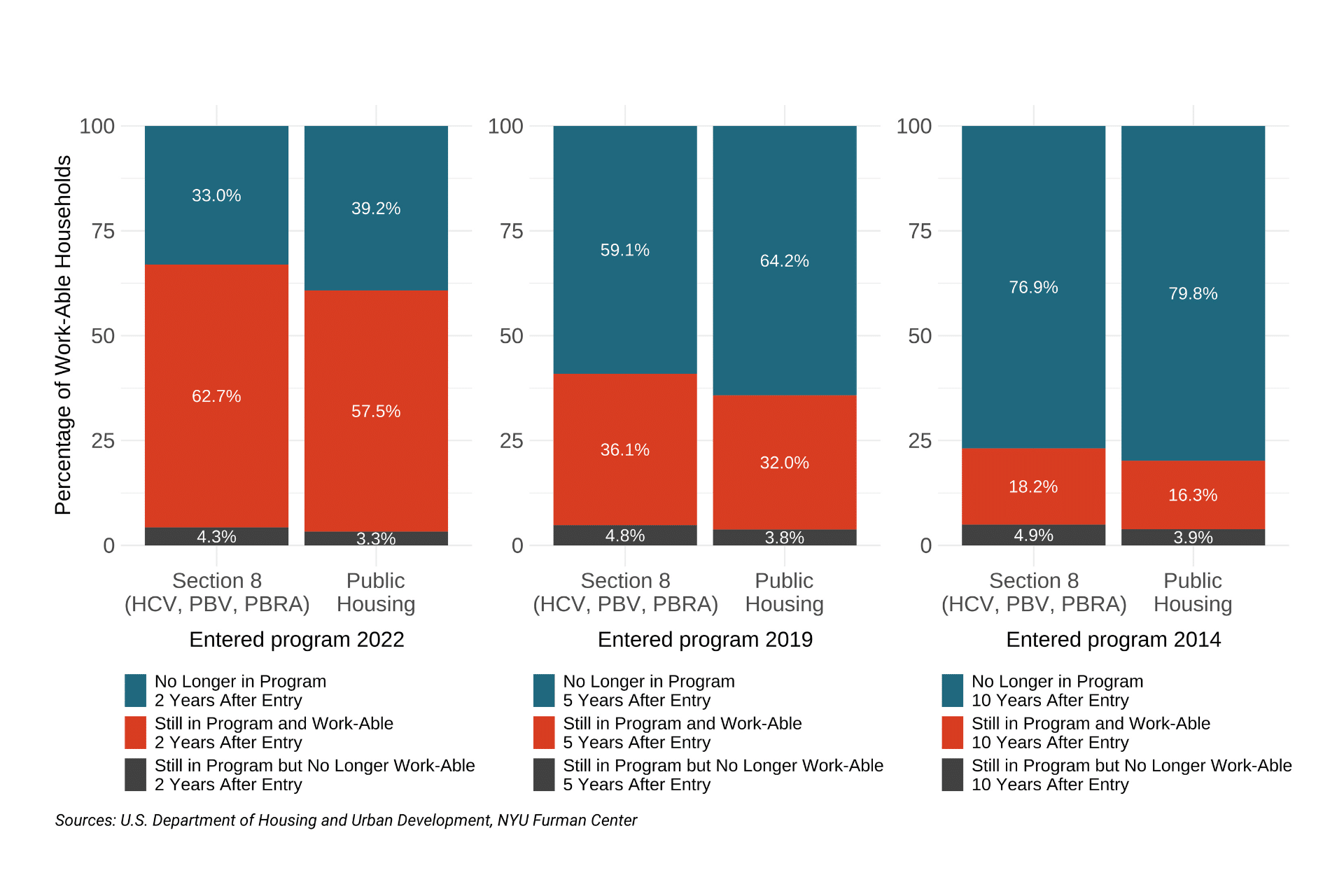

The current assisted population is likely to be disproportionately composed of households who have received assistance for a long time. To understand how many spells of assistance may be terminated by time limits in future years after this initial group of long-term recipients loses their assistance, we need to estimate the share of households entering rental assistance who continue to receive it for more than two years. To answer this question, we examined the cohort of households who either started receiving Section 8 subsidies or moved into public housing in 2022 and were work-able at the time of entry. We then measured the share of those households who were still work-able and in the program 24 months later. We also examined households who were still work-able and in the program who entered in 2019 and in 2014 to determine what percentage of entering households would be affected by five- or ten-year time limits.

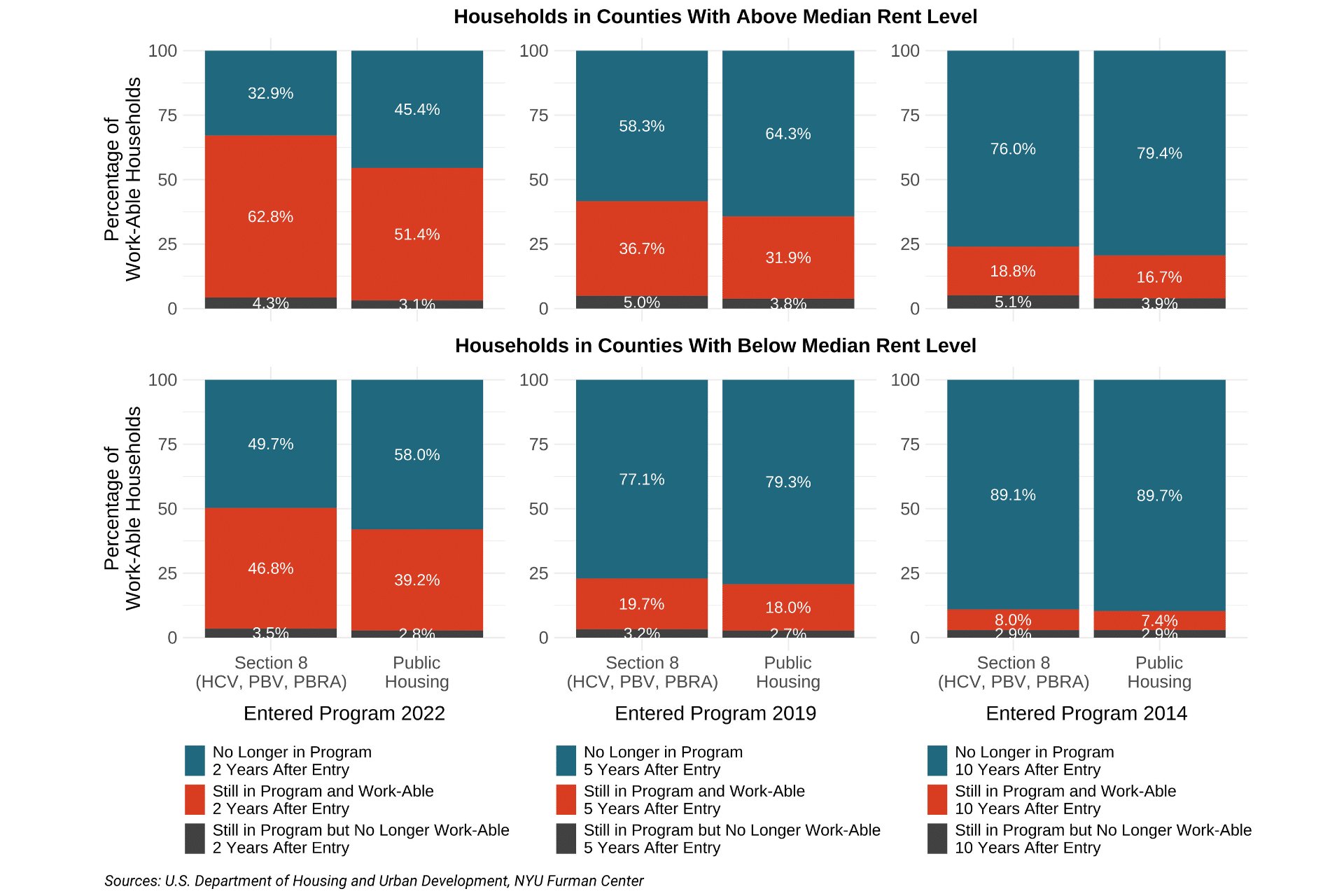

Of work-able households who started receiving assistance in 2022, 62 percent of Section 8 households and 57 percent of public housing households were still in the program and work-able two years after entry (see Figure 7). Approximately a third of work-able households who entered in 2019 were still in the program and work-able five years after entry, and about a sixth of work-able households who entered in 2014 were still in the program and work-able ten years after entry, suggesting that even time limits of more than two years would still affect a large share of households.

Figure 7. Time in Program for Work-Able Households by Cohort

View the data in this spreadsheet

On average, households stayed in housing assistance programs for longer in areas where rents were high, suggesting that time limits would affect larger shares of households in tighter rental markets. Of work-able households who started receiving assistance in 2022, approximately 62 percent of Section 8 households and 51 percent of public housing households living in high-rent counties were still in the program and work-able two years later, compared to 41 and 39 percent living in low-rent counties, respectively.

Figure 8. Time in Program for Work-Able Households by County Rent Level

View the data in this spreadsheet

Note: Median rent level is the median of county-level median gross rents (from the American Community Survey 2023, five-year estimates) for all counties with assisted households.

Conclusion

We estimate that approximately 777,000 households across Section 8 programs and 172,600 public housing households were work-able but not currently earning wage income in 2024. These households, which disproportionately include children, would be most at risk of losing their subsidy if work requirements were imposed. Two-year time limits on all work-able households would also have considerable impacts. If they were applied to current work-able households, approximately 1,129,800 Section 8 households and 265,700 public housing households who have already been in the program for at least two years would lose their subsidy, according to 2024 estimates.

Given the potential scale of the proposed policies, it is notable how few PHAs have tried either work requirements or time limits in the past. Even fewer have conducted rigorous evaluations of these measures. Nevertheless, our scan, literature review, and national data analysis offer some important lessons. One key lesson from past experience is that work requirements and time limits would be costly and complex for agencies as they would have to assess disability status, track work hours, undertake evictions, and manage heightened turnover of units as newly ineligible tenants are forced to exit programs and housing. In addition, terminating subsidies for households who are still relying on them is both politically and organizationally difficult, and PHAs would have to contend with these enforcement challenges.

Our review and data analysis highlight the weighty choices policymakers would face in crafting these policies. First, they would have to decide the length of any time limits and the stringency of any work requirements. Our analysis shows that about 70 percent of currently assisted households with work-able adults have received assistance for more than two years, so a strict, two-year time limit would lead to substantial disruption and dislocation. And though it is outside of the scope of this brief, it is also important to consider how these policies could impact property owners. Landlords in the private rental market who rent to HCV households are accustomed to the long-term structure of the current program. If households lose their subsidy after two years, landlords may be less willing to rent to these households in the first place. This could further decrease the rate at which households offered a voucher successfully lease an apartment, currently at around 60 percent. Additionally, implementing time limits, by increasing the turnover of subsidized tenants, could impact the role that vouchers play in making the development of new affordable housing feasible.

Policymakers would also have to decide who should be subject to the requirements and who should be exempt. They will also need to consider whether the requirements should be different for families with children. By placing restrictions on assistance only for work-able households, which our analysis shows disproportionately include children, work requirements and time limits may gradually shift the composition of households who receive federal rental assistance even further away from children and young families.

Finally, our brief surfaces important policy design choices for PHAs, as they strive to maximize employment, income gains, and successful exits while avoiding unintended harms. Past evidence suggests that they would have to seek ways to ensure households’ awareness of these policies, make it as easy as possible to document compliance, and create explicit hardship policies and processes to avoid penalizing families unnecessarily. They might also consider ways to pair work requirements and time limits with supportive services and complementary policy reforms to aid households’ progress toward financial self-sufficiency. Another policy design choice is whether to provide exit ramps that offer a softer landing for households reaching the end of their time limits or who fail to comply with work requirements. Given the many possible policy structures and the scarce evidence from past experiments, robust monitoring and evaluation will be essential to measure the impacts on both participants and agencies going forward.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ingrid Gould Ellen, Katherine O’Regan, and Martha Galvez for their valuable comments; Tony Bodulovic for developing some of the graphics included in this brief; Finlay Scanlon for research assistance; and all of the PHA leaders and staff who informed this work.

If you have questions about this research, please contact the authors, Claudia Aiken, Director of New Research Partnerships, at claudia.aiken@nyu.edu, and Ellie Lochhead, a doctoral fellow at the NYU Furman Center, at ebl9629@nyu.edu.

Footnotes

[1] Among policies captured in our scan, “adults” were typically at least 18 years old, though some policies also applied to 17-year-olds not enrolled in school. The upper age bracket for work requirements varied from 54 to 62.

[2] Policies also varied in terms of whether minimum work hours applied to each work-able adult in a household, or could be met collectively by some combination of household members.

[3] Some PHAs have implemented a system of incremental sanctions; for example, INLIVIAN first imputes noncompliant households’ income using the state minimum wage, which decreases their rent subsidy, for three months. If the household remains out of compliance at that point, they must pay full contract rent for 180 days. Only then are they subject to an informal hearing which may result in eviction.

[4] SNAP rules generally require people aged 16 to 59 to register for work, participate in SNAP employment training, take a suitable job if offered, and not quit a job or reduce work hours below 30 hours per week without good reason. Exemptions are granted for disability and childcare responsibilities, among other reasons. Able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) aged 18 to 54 face an additional requirement. They must work or participate in a job training program for at least 80 hours a month, or can receive only three months of food assistance every three years.

[5] In June 2018, Arkansas became the first U.S. state to implement work requirements in Medicaid, requiring adults aged 30-49 to work 20 hours per week, participate in “community engagement” activities, or qualify for an exemption.

[6] TANF replaced Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) in 1996 and requires states administering the program to ensure that at least 50 percent of parents work or participate in a set of narrowly defined work activities for 30 or more hours a week per household (or 20 hours, for single parents with a child aged five or younger). States have discretion in how to meet these thresholds and some have imposed sanctions or reporting requirements that are more stringent than others.