The landscape of collaboration on local climate-housing initiatives

California wildfires. Image credit: Getty Images

Last updated on: October 6, 2025

Overview

Housing and climate agencies are similarly tasked with promoting the physical safety of residents and supporting the long-term livability of neighborhoods. Yet despite their complementary aims, their work is often carried out in silos, which limits their effectiveness.

This study offers insights from a national scan of programs and interviews with practitioners, highlighting how some cities are collaborating and outlining valuable lessons that other jurisdictions can apply.

Collaboration has multiple benefits: housing agencies may find new ways to support residential health and affordability, while climate agencies may discover other avenues to pursue their work within an increasingly hostile political environment. Both can increase the reach of their efforts by streamlining service offerings and workflows–an outcome particularly beneficial to small and midsize cities grappling with limited resources. However, a challenge persists: organizations in the housing and climate sectors often have different frameworks for defining and measuring their work or impacts. This misalignment can lead to missed opportunities for leveraging scarce program dollars and maximizing overall impact.

Our climate and housing policy brief established a framework to help practitioners build their vocabulary around the connections between local climate and housing needs. The resource that follows builds on that work by presenting an overview of 54 local programs resulting from the collaboration of climate and housing agencies, along with lessons for small or midsize cities seeking to design or scale similar initiatives. To gain a deeper understanding of how these initiatives are initiated and maintained, we conducted interviews with leaders of 15 innovative programs identified in the scan.

Methods

The foundation of this research is a national scan of programs compiled from local news articles, case studies, and network engagement. While not exhaustive, the scan offers a snapshot of how mostly small or midsize cities connect their housing and climate work.

To be included in our scan, programs must have:

- articulated a blend of climate and housing goals,

- featured collaborative work between housing and climate stakeholders working primarily at the local level, and

- been continuously implemented at the time of our search (i.e., no pop-up, time-limited programs).

After identifying local programs that met our criteria, we used publicly available information from government websites, municipal codes, and press releases to identify each program’s goals, mechanisms, and partners. The Housing Solutions Lab (the Lab) coded goals and mechanisms according to its framework for how housing and climate are connected. Each program could be associated with multiple types of goals and mechanisms.

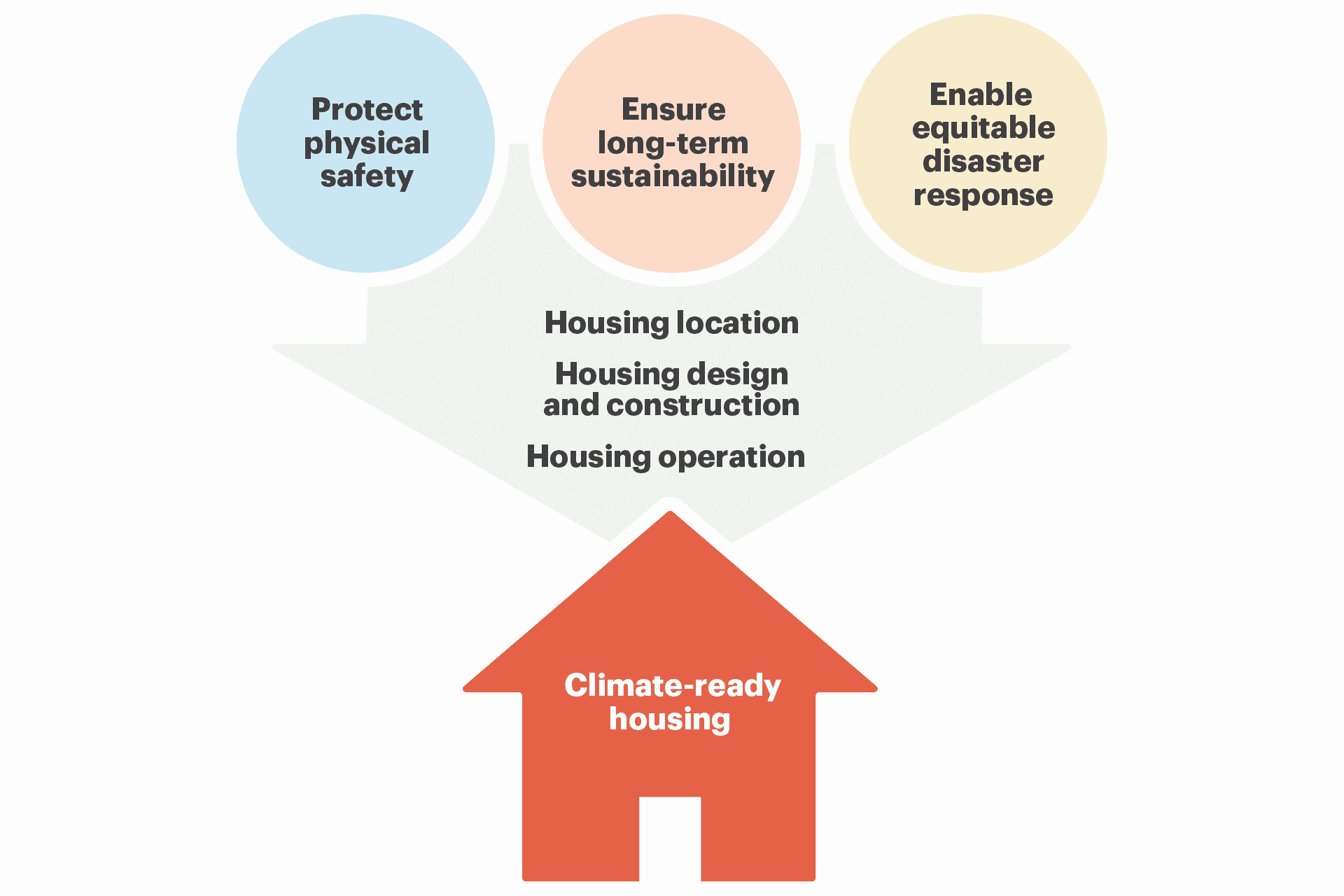

Framework for how housing and climate goals are connected. Source: Housing Solutions Lab.

The resulting scan represents the current landscape of efforts across every region of the United States and each cross-section of climate and housing needs. While this resource is not intended to serve as a comprehensive inventory of every climate-housing program in the country, we are not aware of another initiative that compiles program examples using the same breadth of scope.

Interviews with practitioners were central for gaining insight into how collaborative programs are structured and implemented. We selected practitioners from programs included in our scan, targeting those that approached common types of initiatives with a strong sense of collaboration and those implementing unique programs. Our outreach included practitioners from 26 programs; we ultimately spoke to 17 individuals representing 15 programs.

We used a semi-structured interview protocol for each practitioner. Our conversations focused on the process of establishing and maintaining collaborative programs, which we explored through questions in four categories: funding, collaborative structure, data-driven processes, and engagement with impacted communities. Each of these is important to successfully initiating and sustaining a partnership over time. Sufficient funding is necessary to support the successful operation of any program. Clearly defining tasks and responsibilities between collaborating agencies is key to managing shared workstreams among different entities. Data-driven processes can help organizations develop a shared understanding of their work, gauge the needs of residents, and effectively measure their impact. Lastly, meaningfully engaging residents in program planning processes helps ensure that initiatives effectively address their needs.

After generating initial findings from our scan and practitioner interviews, we conducted interviews with three additional practitioners and researchers. We relied on these conversations to validate our work and refine our takeaways.

How programs frame and achieve their goals

The 54 initiatives included in our scan are a snapshot of the goals, methods, and programmatic approaches in small and midsize cities across the U.S. All five U.S. Census regions are represented, with a slight dominance of programs located in the Midwest and South. These programs utilized various approaches, including municipal climate plans, local regulatory tools, and direct-to-household repair services. The entities implementing these programs also varied: housing authorities, community development departments, and non-profit housing developers were among the housing-related organizations involved in featured programs. The climate-related agencies collaborating with these entities ranged from national nonprofits to city sustainability and resilience offices.

Goals

Goals refer to the overarching motivation or purpose of the program. As we defined in our framing paper, the key goals that connect housing and climate efforts are: protecting the physical safety of residents by reducing exposure to immediate climate risks, ensuring the long-term sustainability of communities by reducing housing-related greenhouse gas emissions, and enabling equitable disaster response and recovery.

More than two-thirds of programs focused on promoting long-term sustainability. These programs aimed to increase energy efficiency and decarbonize the housing stock, for instance, by subsidizing electrification retrofits or updating building performance standards. The popularity of this goal among programs may be due to corresponding large-scale federal investments, such as the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which have spurred long-term, energy-efficiency-based programming at the state and local levels.

The remaining programs were roughly evenly split between disaster recovery and physical safety-oriented initiatives. Collaborative disaster response initiatives included housing buyout programs and programs to help residents repair their homes and make them more resilient after climate events. Our scan identified only ten such programs, possibly due to the fragmented federal funding environment for these initiatives. Multiple reviewers noted how federal disaster-related funds are only dispensed after discrete disasters, making it difficult for many localities to sustain long-term programs.

Programs aimed at enhancing physical safety, or reducing exposure to the negative impacts of climate events, included initiatives to help residents flood-proof their homes, carry out seismic retrofits, and improve insulation against heat and cold. While many cities have home repair programs that have the effect of increasing households’ resilience to climate change, we found relatively few examples specifically geared toward climate-readiness. Federal and state funding streams may also encourage a focus on large infrastructure solutions to promote safety from climate impacts, rather than interventions that target individual homes.

Mechanisms

Mechanisms refer to the discrete opportunities for intervention within the housing sector that practitioners can use to achieve housing-climate goals. As detailed in our framing paper, these include locating housing in less risky, more sustainable areas, increasing the ability of new housing construction to adopt sustainable, resilient design and construction methods, and updating how existing housing operates to be more efficient and resilient.

Most programs addressed housing-climate goals by improving how residential units operate. This was achieved through measures such as energy audits, repairs, or retrofits. The prevalence of this mechanism could be due to the nation’s aging housing stock, as most people live in existing buildings, rather than newly constructed residences. Home maintenance is thus a growing priority for cities, and local governments are increasingly willing to invest public funds into repairing private homes, particularly to benefit low-income homeowners. Rehab and retrofit programs can also lead to utility bill savings for households, offering tangible benefits that transcend political rhetoric surrounding climate change.

Home Energy Tune-ups in Alachua County, FL

The Community Weatherization Coalition in Alachua County, FL is a grassroots community coalition that brings together the City of Gainesville, Alachua County, utility partners, and several non-profit organizations and community members around the mission of helping neighbors save energy and water and reducing their utility bills. As part of this mission, the coalition administers Home Energy Tune-ups that provide energy use assessments and guidance for homeowners and renters, with a focus on low-income households. After the tune-ups, homeowners may also be eligible for more substantial home repair and weatherization work through the coalition’s rehabilitation partners: Rebuilding Together, the Central Florida Community Action Agency, and Alachua County Habitat for Humanity.

The least common way for programs to achieve housing-climate goals was by changing the location of housing. Location-based initiatives aim to address climate concerns by changing where people live–either by relocating current households or focusing new development in specific areas within a community. The infrequent use of this mechanism could stem from several factors. Relocating households away from climate-risky areas can be politically fraught and resource-intensive. Efforts to increase housing density and transit-oriented development, while common talking points among green housing advocates, may face strong resistance from community members. While many local Climate Action Plans included in our scan featured location-based initiatives, tracking the implementation of these elements proved difficult. When reflecting on the progress of their locality’s resilience plan, one non-profit practitioner remarked, “The assumption was that the City was going to be more intentional about what they build, how they build, where they build–and that wasn’t necessarily the case.” Nevertheless, paying attention to the location of housing can be vital for building coalitions that address a city’s long-term response to climate change.

St. Louis, MO, CDBG-DR Action Plan

Part of the City of St. Louis’ Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) Action Plan includes a buyout program that allows homeowners to relocate from risky areas in the city’s floodplain. This plan was adopted in response to severe flash flooding in the summer of 2022. As part of the plan, the city aims to purchase 20 homes at risk of repeated flooding and convert these properties into water-absorbing greenspace. With a total budget of over $5 million, the program allocates a maximum award of $350,000 per property, with an average award of $225,000. Core goals of this program include minimizing future harm to safety, life, and property, and preventing harmful displacement where possible.

Initiatives

Cities pursued the goals and mechanisms detailed above through many types of initiatives, including resilience hubs, or community facilities that centralize and coordinate climate services; building performance standards; flexible local funding sources; workforce development programs; and residential design assistance programs. Retrofit and rehab programs were the most common among the initiatives captured in our scan.

Our scan also includes a small sample of municipal Climate Action Plans. These plans outline a locality’s strategy for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating or adapting to the negative effects of climate change. They may propose all of the mechanisms and many of the initiatives discussed above. But while plans like these are increasingly common, they vary greatly in their substance and enforceability. Some interviewees reported that their community’s plan failed to define resources for implementation. In many cases, it was also difficult to identify concrete progress or achievements pursuant to the housing-related strategies in these plans.

Houston, TX, Climate Action Plan

The City of Houston, TX, adopted its Climate Action Plan in 2020. The plan sets a goal of citywide carbon neutrality by 2050. It aims to accomplish this through twelve goals in the areas of transportation, energy transition, building optimization, and materials management. The plan’s housing-related goals include reducing building energy use and expanding investment in energy efficiency.

Skokie, IL, Environmental Sustainability Plan

In 2022, the Village of Skokie, IL, adopted its Environmental Sustainability Plan. The plan establishes citywide strategies to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Strategies encompass increasing residential density, reducing Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT), improving community-wide energy efficiency, developing emergency response systems, and updating zoning and design standards to increase residential resilience. The plan also features an appendix on funding strategies for these sustainability initiatives, including bonds, taxes, municipal fees, and state and federal grants.

How collaborative programs are established and sustained

Our interviews with practitioners offered insight into how collaborative programs went about structuring their work to achieve shared goals. To explore the details of their work, our conversations focused on four central program design considerations: collaborative structure, funding, data-driven processes, and community engagement throughout the program planning process.

Structure

Agencies coordinated with their program partners in a variety of ways. Below, we detail four common structures for collaboration.

Convene

- Definition: An organization primarily responsible for coordinating work and communication among a network of agencies and service providers.

- Common context: Programs with a high volume of complex, time-sensitive projects requiring several agencies’ skills and labor.

- Example: In Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia Energy Authority’s Built to Last program allows households to access a variety of home repair services through one front door. The Philadelphia Energy Authority serves as the “administrative backbone” that helps identify each household’s needs and coordinates service provision among over a dozen organizations.

Specialize and replicate

- Definition: An organization focuses on building expertise in a specific funding source or service model, then contributes this skillset to multiple local partnerships.

- Common context: Nonprofits with a focused mission, limited resources, and an interest in scaling impact.

- Example: The Home Energy Tune-up program, a DIY weatherization program, is the flagship offering of the Community Weatherization Coalition. The Florida nonprofit uses the expertise and volunteer base they’ve developed for this program to support several partnerships and programs, including the Alachua County Energy Efficiency Program and the EMPOWER Coalition.

Mediate

- Definition: An agency facilitates communication between external stakeholders–often between residents and technical program staff.

- Common context: Programs that help residents navigate complex processes. Mediating agencies typically carry both technical expertise and experience with direct engagement.

- Example: Sustain Dane’s Efficiency Navigator Program provides financial and administrative assistance to help owners of naturally occurring affordable housing undertake energy-efficient retrofits. Sustain Dane, located in Wisconsin, helps build trust between their municipal partners and property owners and facilitates communication between property owners, energy assessors, and contractors.

Connect programs

- Definition: Organizations set up systems to help their distinct initiatives achieve a seamless experience for users. May take different forms depending on the program type: referrals, coordinated incentives, internal alert systems, etc.

- Common context: Agencies with established, high-capacity projects that serve overlapping beneficiaries.

- Example: Denver, CO’s Office of Climate Action, Sustainability and Resiliency uses a portion of its Climate Protection Fund to offer incentives for sustainable building design. These incentives are structured to encourage behaviors that Denver’s Department of Community Planning and Development aims to include in a future building code.

Funding

Dedicated funding streams were often the catalyst for housing agencies to participate in housing-climate efforts. As noted previously, federal funds often played a significant role in establishing dedicated funds for housing-climate action. At the same time, a number of cities used locally-sourced funds to establish robust collaborative efforts in their community. These local sources include:

Local utilities

How: In some cases, local utilities offered funding to households for solar installation and energy-efficient retrofits through federally funded or state-mandated programs; local nonprofits then became specialists in helping households access and use these funds. In other cases, municipal utilities set aside a percentage of their profits to create and implement programs. The goals of these programs depended on the type of utility, ranging from floodplain buyouts implemented by a stormwater utility to energy-efficient design assistance offered by an energy utility.

Pros: As revenue-generating non-profits, municipal utilities have access to funds that, like a city’s general funds, are committed to public benefits. However, a municipal utility can exercise more discretion in how its profits are used. An engineer and program manager at a municipal energy utility noted that, even when the economics of energy efficiency became complex, “We have to justify spending that money in other ways. The citizens of [the city we serve have said] ‘we want to cut carbon…we’re willing to spend that.’ You can either do it by utility programs or you can do it by other [municipal] sustainability programs. Turns out, utilities have a lot of money, so it’s easier to get money from that.”

Depending on the state, investor-owned energy utilities may also have funds dedicated to support home energy efficiency for low-income residents.

Cons: While municipal utilities have some flexibility in what programs they fund, these allocations are susceptible to change based on the local political environment. One home repair program, led by a non-profit organization, experienced a sudden loss of funding after several years of financial support from its local utility. This change occurred following a restructure of the utility’s leadership by the state. A representative from the program stated, “We’re victims of a political fight that’s been ongoing in this community for many years.”

When utilities are investor-owned, their goals may not align with those of local government. A municipal sustainability manager noted that this was particularly true in their city, which faced extreme temperatures and an older housing stock. Within this context, buildings often require major systems upgrades to electrify them and lower energy bills for residents. Investor-owned utilities may see little incentive to invest in such upgrades, which could reduce their revenue, while local governments are more likely to value the long-term benefits of increasing residents’ resilience and reducing emissions.

Local sales taxes

How: Voters approved the expansion of sales taxes to fund climate action in a few cities. Funds were either allocated to various city agencies, evaluating requests using a city-drafted funding strategy, or split between a pre-defined group of programs.

Pros: New sales taxes are typically easy to collect based on pre-existing systems. Under ideal conditions, they can also generate large sums of money relatively quickly. A sustainability director emphasized the local sales tax-based climate fund’s critical role in building their office’s capacity: “We’re not getting 40 or 50 million dollars from any other source for climate action. There is no money.”

Cons: Revenues can be volatile during recessions. Denver’s recent audit of its Climate Protection Fund highlighted how the administration and oversight of funds can be labor-intensive, particularly when funds are allocated among several departments, programs, and activity types.

Green banks

How: These institutions helped climate-conscious housing development projects leverage capital. They also acted as fiscal agents, enabling government agencies to pay for direct services offered to households.

Pros: Their specialty in climate-related capital and development makes green banks better able to take risks on green infrastructure projects compared to traditional banks. They also often have more expertise in working with complex federal funding streams. A director who oversaw a residential development with an ambitious sustainability agenda noted the central role of a green bank in using federal tax credits. “Most of the [traditional] banks will be like, ‘That’s kind of risky. What if these houses don’t get built? And what if these businesses don’t get built?’…But the green bank said, ‘We trust that the [interviewee’s organization] is going to deliver the development’…Without the loan from [the green bank], we don’t have the money upfront to make [the development] happen,” they said.

Cons: Green banks were rarely the sole source of capital for projects. The green-bank-funded programs we discussed in interviews needed other sources of revenue to pay back their loans or serve as pass-through funds.

Data

Sharing data between agencies was not common within the programs featured in our scan. While individual agencies tracked their own internal metrics, continuous data sharing between collaborating agencies was often not seen as necessary to sustain program work over time.

While many programs were able to serve households without data sharing, a recent audit of Denver’s Climate Protection Fund suggests that finding ways to strategically share and review data over time can help ensure programs achieve their intended impacts. Some ways that programs in our scan integrated data-driven processes into their work included:

- Aligning metrics among project team members. A housing development project that featured advanced green energy infrastructure found that its housing development partners were accustomed to analyzing impact on a per-unit basis. In contrast, the green energy specialists were used to assessing project-wide impacts. The team dedicated extra time and communication between project partners to define mutually beneficial metrics and ideal goals for costs and benefits.

- Updating program metrics to motivate desired behavioral changes. A green design program changed the structure of its incentives for energy-efficient building design. The program formerly awarded funds based on energy cost savings, but now pays out incentives based on the reduction in BTUs used to heat the building. This made it easier to incentivize the conversion from gas furnaces, which provide cheap energy but are inefficient, to heat pumps, which are more efficient even though they rely on more expensive energy.

For more ideas on how to integrate data into housing-climate projects, see the Lab’s brief on using publicly available climate data to inform housing decisions.

Equity and engagement

Many initiatives did not center resident engagement processes within their programmatic approach. This may reflect the many barriers to equitable engagement in the housing sector and the challenges of combining technical knowledge and community-sourced knowledge within climate action. Still, researchers emphasized the role of meaningful engagement in creating programs that effectively address residents’ needs.

Some ways that programs in our scan engaged residents in the planning processes included:

- Design workshops: The Houston Community Land Trust, in Texas, uses information from interactive design charrettes with community members to inform the creation of a portfolio of climate-ready home designs through the Finding Home Initiative.

- Involving community partners at multiple levels: A few partnerships, such as Sustain Dane’s Efficiency Navigator program, used feedback from community partners to inform local outreach and program design, leading to changes in data collection and communication with program participants.

For more ideas on how housing programs can meaningfully engage community members, see the Lab’s resource on Engaging the community in a local housing strategy.

Emerging models for climate-housing collaboration

In many contexts, cities will find it easier to build long-lasting, impactful programs when they utilize initiatives and resources that already exist locally. The following initiatives are helpful starting points to consider when establishing or deepening comprehensive, local approaches to coordinating climate and housing goals.

Rehabilitation and retrofit programs

- Why: Rehab programs are common across the country. However, many of them do not address the full range of housing’s climate-related concerns, such as physical safety, sustainability, and disaster recovery. Additionally, existing programs are often underfunded and unable to meet the full needs of their communities. Thus, evaluating how current programs and systems can build on their current successes to address comprehensive housing-climate concerns is one step likely to be accessible for many communities.

- How: Designate one agency as the “convener” to coordinate household intake and rehab project timelines; set up referral pipelines between regulatory processes, rehab programs, and other related services.

- Examples:

Philadelphia, PA’s Built to Last program coordinates the delivery of services offered by over a dozen local organizations. By combining basic home repairs with energy efficiency retrofits and other services needed to support healthy residential environments, the program helps boost the impact and reach of each participating agency.

In the past, housing development and disaster recovery nonprofits in Alachua County, FL, met monthly to review a shared list of local low-income households receiving services from each organization, identify their needs, and coordinate future work among participating organizations based on expertise, funding availability, and staff capacity. While a unique model among housing-climate initiatives, this approach, known as case conferencing, is commonly used within the homeless services sector.

Flexible and coordinated financing

- Why: Establishing a new, dedicated source of funding at the local level can provide climate-housing collaborations with a stream of resources that is more reliable and flexible than state and federal funds. On the other hand, cities can also work to increase the impact of existing dollars by coordinating the administration of state and federal grants received across different agencies.

- How: Seek voter approval for local sales tax-funded climate initiatives through ballot measures and restructure local government to centralize the administration of climate-related dollars from state and federal sources.

- Examples:

Portland, OR’s Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund supports community-driven projects that promote sustainability and resilience, particularly among underresourced residents. The fund raises money from a one percent surcharge on local sales from large retailers and lists supporting energy efficiency in housing as one of its funding priorities.

In Lee County, FL, the Office of Strategic Resources and Government Affairs manages federal grants for various countywide infrastructure projects and disaster recovery initiatives. The creation of the office marked a shift in the county’s approach to disaster recovery: in the past, temporary committees would plan and oversee the use of federal aid. However, as the county experienced more frequent disasters, establishing the office as a permanent entity allowed for better organization and coordination of funds.

Resilience hubs

- Why: Resilience hubs can be effective ways to streamline access to existing community resources, opening up opportunities to reach new households and pursue actions that support household safety, sustainability, and post-disaster recovery.

- How: Identify government agencies and nonprofits providing direct services and informational resources concerning household climate resilience and recovery; establish easy-to-use methods for accessing these resources, such as linking different programs or centralizing contact points, among other effective strategies.

- Examples:

Boulder County, CO’s Rebuilding Better is a platform that compiles guidance on home construction, financing opportunities, and access to expert advisors to victims of the Marshall Fire. The resources provided assist with rebuilding homes that are both resilient to future fires and energy-efficient.

In Detroit, MI, the Detroit Resilient Eastside Initiative is a network of community-driven resilience hubs that help residents access critical services year-round. One of the lead organizations involved, Eastside Community Network, worked directly with residents and community organizations to define the community’s resilience needs. Based on these needs, the resilience hubs help residents with internet access, transportation, food, and medical supplies. Additionally, residents can receive support with their applications for federal disaster assistance.

Getting started with climate-housing collaboration

Cities currently face a particularly challenging political environment for climate-related action. As of summer 2025, the federal government has stalled or reversed several housing-related funds established in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, rolled back states’ ability to regulate air pollution, and threatened to eliminate the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). As local governments increasingly navigate federal policy that is hostile to climate action, the following insights can help build buy-in among local stakeholders:

- Highlight housing affordability, rather than climate-forward impact. While some organizations are dedicated to helping their cities navigate climate change, their external programming features language emphasizing reductions in household energy and reconstruction costs to establish broader appeal.

- Focus programming on current climate impacts, rather than future climate projections. The damage caused by wildfires, flooding, and other natural disasters is undeniable in affected cities. Although focusing on the immediate effects of climate change does not directly support a city’s long-term environmental sustainability, some programs have successfully used this approach to overcome political challenges to climate action. This strategy has helped in building local coalitions and implementing programs that can serve as the foundation for broader change.

- Establish consistent ways to share data and communicate insights. Data-driven approaches to defining shared goals and articulating program benefits can help build narratives that cross traditional professional boundaries.

- Enhance engagement practices. As federal cuts to climate-related programs create greater needs at the local level, effective communication and collaboration with communities will become more crucial. Engagement not only improves program design but also ensures that beneficiaries truly feel the impact of new initiatives in their daily lives.

Acknowledgements: This report was authored by Aisha Balogun, with research, writing, and editorial support from Claudia Aiken, Tony Bodulovic, Nora Carrier, Martha Galvez, and Jess Wunsch. We extend our deep gratitude to all of the local government and nonprofit leaders who took the time to speak with us about their efforts at the intersection of housing and climate policy.