On this page

Federal programs for affordable housing

Funding a local housing strategy

August 8, 2025

While cities, towns, and counties have an important role to play in funding affordable housing, most of the financial support for it has historically come from the federal government. Federal programs finance new construction, invest in underserved neighborhoods, support home repairs, and help low-income tenants pay their rent. The impact of these resources can be multiplied, as federal dollars are often used to leverage additional state, local, or private funds for affordable housing.

This page provides an overview of major federal funding streams for affordable housing as of June 2025, broadly categorized into funds that support multifamily construction and preservation, rental assistance programs, and place-based investments. Other funding sources not included in this brief include state funding sources and funds dedicated to addressing homelessness. Learn how local resources can be used to augment federal funding for affordable housing.

Some programs have a narrow scope while others offer more flexibility. Additionally, the methods for distributing these funds vary significantly, including options like appropriations, block grants, and competitive grants.

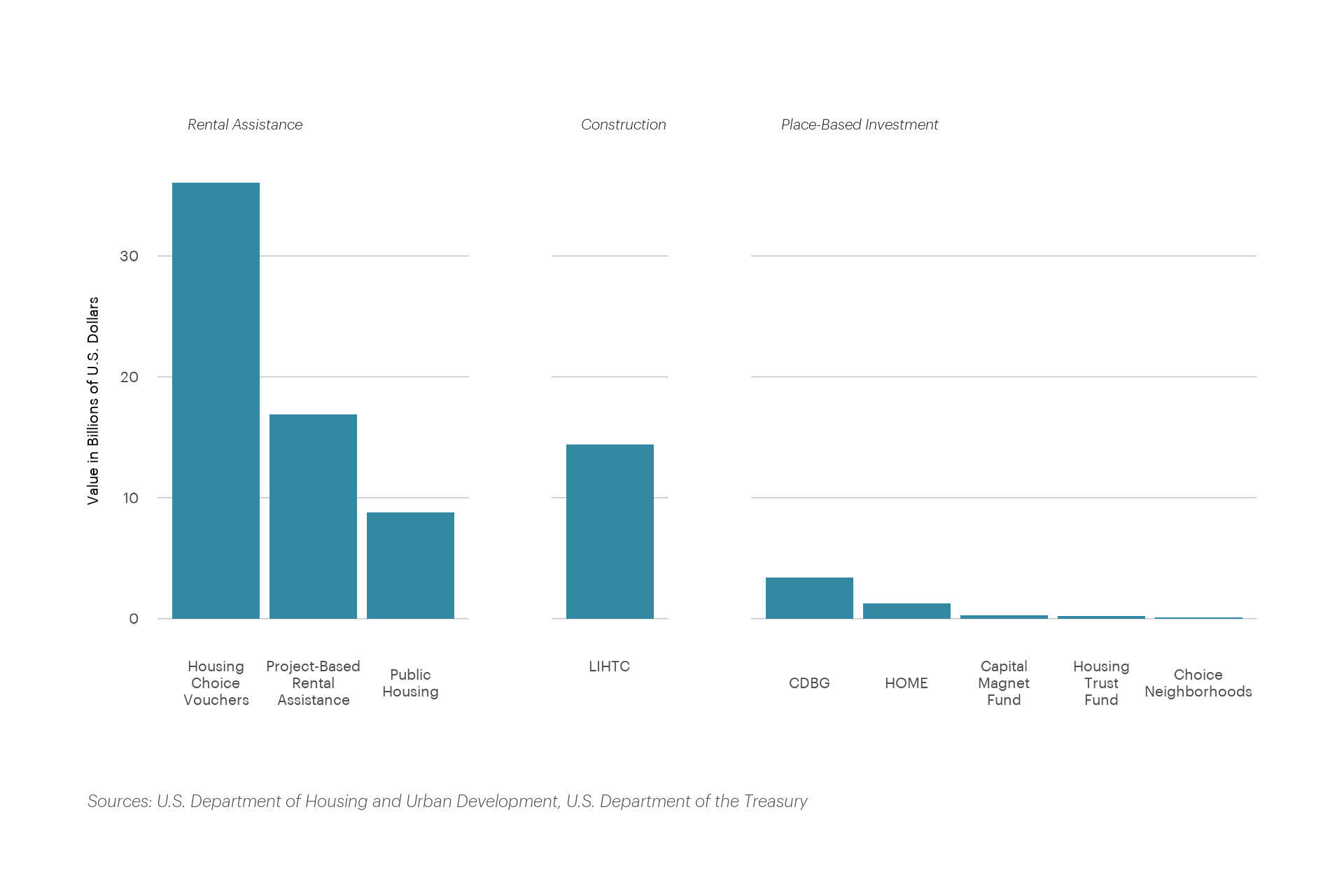

The figure below gives a sense of the size and relative scale of these programs as of fiscal year (FY) 2024:

Figure 1. Federal Programs for Affordable Housing

View the data in the Google Sheet

Please note that these programs rely on the congressional budget and appropriations process, which can lead to varying allocations each year based on federal priorities. The federal government may also revise the requirements governing their use. Nevertheless, these federal initiatives have been reliable sources of funding for affordable housing for decades for cities and states.

Aside from the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program, which is administered by state and local housing finance agencies, most of these programs are administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). HUD has also funded a variety of smaller programs, many of which focus on specific activities or goals such as providing support for lead abatement and healthy homes and promoting economic self-sufficiency among residents of subsidized housing. A number of other federal agencies also fund affordable housing activities. Most notably, the U.S. Department of Agriculture administers programs that fund single-family and multifamily housing in rural cities, towns, and counties through the Rural Housing Service, described below. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services also provides funding, sometimes in partnership with HUD, to support housing and services for people experiencing homelessness.

Options for applying these and other funding sources to specific local housing goals and activities, such as supporting home repair, affordable rental housing development, or homeownership programs, can be explored in our federal funding directory.

Multifamily construction and preservation

This section includes federal funding sources primarily dedicated to affordable housing construction. Other programs on this page could fund construction and preservation, but are also used for other housing activities. Multifamily construction financing may also be supported by the reliable income stream that rental assistance programs provide.

Low-Income Housing Tax Credits

The largest source of federal support for the creation and preservation of dedicated affordable housing is administered by state and local housing finance agencies based on regulations issued by the U.S. Treasury Department. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program is an indirect subsidy program that provides an incentive for private companies to invest in affordable housing through a dollar-for-dollar reduction in federal income tax liability. Investors receive the credit over a 10-year period, and projects financed with LIHTC equity must remain affordable for a period of at least 30 years (although some states have adopted longer affordability requirements). Since the program was created in 1986, 3.7 million LIHTC units have been placed in service in more than 54,000 projects.

As of 2025, there are two types of LIHTCs: 9 percent credits and 4 percent credits. Both are allocated by state and local housing finance agencies. The 9 percent LIHTC is typically used for new construction and larger renovation projects. It is awarded on a competitive basis, in accordance with the preferences and priorities outlined in the Qualified Allocation Plan of the state housing finance agency.

The allocation of 9 percent LIHTCs for each state is determined annually using a population-based formula. For 2025, each state’s LIHTC tax credit limit is $3 per resident or at least $3.46 million. In high-cost areas, the 4 percent LIHTC is used primarily for preservation and acquisition-rehab projects, although in other areas it can be used for new construction. This tax credit is automatically awarded to affordable housing projects that are supported with private-activity bonds. In 2025, state allocations for tax-exempt private-activity bonds amounted to either $388.8 million or $130 per resident, whichever was greater.

To comply with the requirements of the LIHTC program and prevent the recapture of tax credits, projects must set aside at least 20 percent of units for tenants earning less than 50 percent of the area median income (AMI), or 40 percent of units for tenants earning less than 60 percent of AMI, throughout the 30-year compliance period. Project sponsors often set aside a much larger share of units as affordable housing to increase the competitiveness of their applications and the amount of tax credit equity they can raise. Many projects even meet the LIHTC requirements in 100 percent of their units. While generally more affordable than market-rate units, rent levels at LIHTC developments are typically too high to be affordable to extremely low-income households without additional subsidy. Cities, towns, and counties often attach project-based vouchers (PBVs) or other federal or state rental assistance to some or all units in a LIHTC development to reach individuals and families who require deeper affordability.

Rental assistance programs

Rental assistance can make housing affordable for families by paying some or all of their rent. Tenant-based programs subsidize market-rate units selected by households. With project-based rental assistance programs, the subsidy is attached to specific buildings or units.

Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers

Federal rental assistance is provided primarily through HUD’s Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, also known as Section 8, which assisted over 5 million people in more than 2.3 million families annually as of December 2024. The program is implemented by local and state public housing agencies. Voucher holders receive a subsidy that they can use at any privately owned rental unit that meets program guidelines and has an owner willing to participate in the program. Because the assistance moves with the household, rather than remaining attached to a particular unit, tenant-based rental assistance can be a particularly effective tool for increasing low-income families’ access to low-poverty, resource-rich neighborhoods. HCVs are also very flexible. Public housing agencies have the flexibility to “project-base” a portion of their vouchers, attaching them to specific units to provide ongoing affordability, and to allow vouchers to be used for home purchase.

All voucher holders must have incomes, at the time of enrollment, that do not exceed 80 percent of AMI. At least 75 percent of the households newly enrolled in the program each year must be extremely low-income households with incomes that do not exceed 30 percent of AMI or the federal poverty level, whichever is higher. Participating households are required to contribute 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities, and the housing agency pays the balance (up to a locally defined maximum known as the voucher payment standard) directly to the landlord. Agencies may also set minimum rents. Demand for vouchers far outstrips supply, and most public housing agencies either maintain long waiting lists for the program and/or use a lottery to determine which households may join the waiting list.

Subject to congressional appropriations and budget availability, HUD provides annual funding to public housing agencies to renew HCVs currently in use. However, due to changes in funding policies, sequestration (a budget procedure that cancels previously allocated funds), and continuing resolutions that freeze program funding, available funds have at times been inadequate to renew all existing vouchers. Industry groups estimate the cost of fully renewing all vouchers in FY 2025 will be $30.6 billion.

Other tenant-based rental assistance programs use HCVs to serve populations with specific needs within the mainstream voucher program. The HUD-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) program, for example, is jointly administered by HUD and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and combines HCV rental assistance with supportive services delivered by the VA to provide stable housing for veterans experiencing homelessness. Since the program’s creation in 2008, more than 112,000 HUD-VASH vouchers have been awarded. Another specialized tenant-based rental assistance program – the Family Unification Program (FUP) – provides HCVs to families for whom the voucher will help prevent or end a child’s placement in out-of-home care due to housing instability or inadequate conditions. FUP is administered by public housing agencies in partnership with public Child Welfare Agencies, which provide supportive services to participating children and families. The program currently assists about 30,000 households. Additionally, the Emergency Housing Voucher (EHV) program was created in 2021 as part of the American Rescue Plan Act. EHVs offer tenant-based rental assistance for individuals and families experiencing homelessness, at-risk of homelessness, or fleeing domestic violence. EHV funds will only cover families through 2026, however, leaving public housing agencies to find other ways to sustain support for these households.

As mentioned previously, public housing agencies also have the option to project-base some of their voucher allocation. Public housing agencies contract with landlords for up to 20 years to attach PBVs to specific units and rent to low-income families. Public housing agencies can generally project-base up to project-base up to 20 percent of their voucher allocation – in areas where vouchers are “difficult to use,” public housing agencies can project-base another 10 percent. As of 2024, there are over 500,000 tenants in about 290,000 units nationwide using PBVs. PBVs offer less mobility than tenant-based rental assistance, but once a household has lived in a PBV unit for a year, they can opt to move with the next available tenant-based voucher. Compared to traditional HCVs, PBVs can improve access to supportive services for voucher holders and can create more mixed-income housing in communities. Public housing authorities can also place PBVs in lower-poverty neighborhoods to grant families access to higher-opportunity areas.

Project-based rental assistance programs

Federal project-based rental assistance is provided primarily through HUD’s Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance program (PBRA). Although Congress repealed authorization for the construction of new units under the program in 1983, it continues to renew Section 8 PBRA contracts for homes serving nearly 2 million people in approximately 1.2 million households as of 2024. The program is implemented by private owners of multifamily rental housing. Because the assistance stays attached to the unit, project-based rental assistance can be a particularly effective tool for creating and preserving affordable housing in high-cost or gentrifying areas. In FY 2024, HUD funding for PBRA programs was $15.9 billion.

Project-Based Rental Assistance is distinct from project-based vouchers, where public housing agencies (PHAs) opt to attach some of their voucher funding to a specific unit. The programs are similar in many respects but are funded and administered differently. Both provide low-income families with a deep rental subsidy to help them afford the costs of rent and utilities. The main difference is that project-based vouchers are administered by PHAs and overseen by HUD’s Office of Public and Indian Housing, while PBRA contracts are between private owners and HUD’s Office of Multifamily Housing, with no involvement by the local PHA.

To be eligible for Section 8 PBRA, households must have incomes, at the time of enrollment, that do not exceed 80 percent of AMI. At least 40 percent of assisted units must be reserved for extremely low-income households with incomes that do not exceed the higher of 30 percent of AMI or the federal poverty line. Participating households contribute 30 percent of their income or a minimum of up to $25 each month (whichever is greater) for rent and utilities, and the housing agency pays the balance due directly to the landlord. In 2023, two-thirds of Section 8 PBRA units were occupied by households headed by a person who was a senior or had a disability.

HUD has also provided project-based rental assistance to private owners of multifamily rentals through several smaller programs, including the Rent Supplement Program, the Rental Assistance Payments program, and the Section 8 Moderate Rehabilitation program. Many of these programs have been phased out or consolidated over the years, and while no new units are being created, HUD continues to provide rental assistance for the remaining projects under existing contracts even as it seeks to convert these properties to Section 8 through the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD).

Preserving units with project-based rental assistance as affordable when their contracts expire is a major challenge for many cities, towns, and counties, particularly for projects located in gentrifying neighborhoods. While existing residents typically receive tenant-based assistance that allows them to stay in their homes, long-term affordability in the development is lost when income-eligibility restrictions are lifted and the units are no longer available to serve other low-income families. Some cities, towns, and counties have created preservation inventories to enable early identification and intervention to preserve units at risk of being lost.

Public housing operating fund and capital fund

Public housing is affordable housing that is owned and operated by local public housing agencies. About 1 million households live in public housing, most of whom have extremely low incomes. About one-third of households in public housing are families with children. All residents must have incomes that do not exceed 80 percent of the AMIe at the time of admission, and at least 40 percent of new public housing residents each year must be extremely low-income, with incomes that do not exceed the higher of 30 percent of AMI or the federal poverty level. Residents generally make contributions toward rent and utilities equal to 30 percent of their income, their welfare shelter allowance, or a minimum rent established by the public housing agency of up to $50, whichever is greatest. Alternatively, residents may choose to pay a flat rent that does not vary with income.

Public housing agencies receive funding for public housing developments in two streams: the capital fund and the operating fund. The public housing capital fund is intended to address properties’ capital needs. Eligible activities include non-routine maintenance, safety and security measures for residents, development and reconfiguration of public housing units, modernization work, and costs related to site improvements or demolitions for modernization or redevelopment projects. The operating fund helps to make up the difference between residents’ rent payments and the cost of day-to-day operations. This includes expenses for routine and preventative maintenance, staff salaries, and insurance.

Public housing funds are distributed by HUD to public housing agencies on a formula basis and in amounts that depend on congressional appropriations. For many years, the amount of funding made available through the operating fund has fallen short of the amount specified in the public housing operating formula. As a result, agencies receive a reduced, prorated amount. Similarly, funding for the public housing capital fund has likewise been inadequate to keep pace with the cost of addressing capital needs in public housing developments. This deficit, estimated at $115 billion in 2023, is growing by $3.4 billion each year and poses a threat to the ongoing viability of public housing stock. In FY 2012, Congress authorized the RAD program to help address these shortfalls. RAD allows public housing agencies to convert 455,000 units that are subsidized through the public housing program to Section 8 assistance, either through project-based rental assistance or project-based vouchers.

Place-based investments

The federal government distributes funds supporting affordable rental housing and homeownership to towns, cities, counties, tribal entities, states, public housing agencies, nonprofit housing organizations, and housing finance agencies. Some of these funds support housing as part of a place-based investment strategy or a suite of community development activities, while others have very specific uses.

Choice Neighborhoods

Choice Neighborhoods is a competitive grant program that supports the transformation of housing and neighborhoods in targeted areas. A successor to the HOPE VI program, HUD created Choice Neighborhoods in FY 2010. Choice has distributed $1.8 billion in grants to over 40 cities to create more than 30,000 units of mixed-income housing, but funding was reduced in FY 2024 to $75 million from $350 million in FY 2023. Choice Neighborhoods’ Implementation Grants fund the replacement of severely-distressed public housing and privately-owned HUD-assisted properties with energy-efficient mixed-income properties, either through rehabilitation or demolition and new construction. All housing redevelopment activities must be implemented in conjunction with a comprehensive neighborhood revitalization plan, called a Transformation Plan. The Transformation Plan describes how the grantee will address community problems, increase opportunity, and improve social outcomes for residents of the redeveloped housing and surrounding neighborhood in a variety of areas, including education, employment, and health. (Smaller planning grants are available to support preparation of a Transformation Plan.) Program funds may be used to provide supportive services and make improvements to the surrounding community.

Eligible grantees include public housing agencies, local governments, and tribal entities. Private owners of HUD-assisted properties and private developers, whether for-profit or non-profit, may apply in partnership with any of these entities. Redeveloped units must be replaced on a one-for-one basis, either on-site, in the target neighborhood, or up to 25 miles away if the new neighborhood has a low poverty level, a low concentration of minority residents, and satisfies amenities requirements. Under certain conditions, project sponsors may also replace up to half of the units with Housing Choice Vouchers. As of 2022, these conditions included: 1) a “loose” rental market relative to population change (areas with <1 percent population growth need a vacancy rate greater than 5.9 percent); 2) at least half of vouchers currently in use must be in neighborhoods with poverty rates below 20 percent. The Choice Neighborhoods mapping tool has an “Off-site Replacement Housing” tab that can be utilized by registered users to check these conditions. Residents who are relocated during the redevelopment have a right to return to the newly redeveloped property, and program sponsors must track residents until the new housing is fully occupied. Choice Neighborhoods also includes a requirement for ongoing resident involvement from the planning stages through implementation.

HOME Investment Partnerships Program (HOME)

The HOME program is a block grant provided by the federal government directly to large cities, towns, or counties, as well as to states for distribution to areas that do not receive direct funding. HOME funds can be used for a variety of housing-related activities, including home purchase and rehabilitation assistance, site acquisition or improvement for the development of affordable rental or owner-occupied housing, and tenant-based rental assistance. Sixty percent of funds are distributed by formula to cities, towns, counties, and consortia of local governments, and the balance goes to states, which can fund projects directly or issue sub-grants to local jurisdictions that are ineligible for their own direct allocation. HUD’s allocation formula is based on a range of factors, including the inadequacy of the local housing supply, poverty levels, and fiscal distress, among others.

In FY 2025, the HOME program received a total funding of $1.25 billion, aimed at supporting low-income households. Program rules require that 100 percent of HOME funds be used to assist households at or below 80 percent of AMI, with lower income requirements set for certain eligible activities. At least 15 percent of a participating jurisdiction’s HOME allocation must be set aside for housing that is owned, sponsored, or developed by a Community Housing Development Organization (CHDO). CHDOs are private, nonprofit, and community-based organizations with capacity to develop affordable housing. All HOME funds used for affordable housing must be matched by state or local resources or private contributions, amounting to at least 25 cents for every dollar of HOME funding. States are guaranteed either a formula allocation or a minimum grant of $3 million, whichever is higher. Local jurisdictions or consortia must qualify for a formula allocation of at least $500,000 to receive direct HOME program funding. In FY 2024, all 50 states, as well as the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, received HOME grants with a median award of about $8 million. Additionally, 632 localities and consortia also received HOME funds with a median award of about $660,000.

Community Development Block Grants (CDBG)

Since 2005, CDBG funds for housing activities have served about 2 million households. CDBG funds can be used for a variety of eligible activities related to housing and community development. Eligible CDBG activities include supporting affordable rental housing and homeownership, performing rehabilitation and emergency repairs to owner-occupied and rental homes, providing downpayment and closing cost assistance, acquiring and constructing rental housing, and offering certain housing-related services, such as housing counseling, among others. Seventy percent of funds are distributed by formula to “entitlement jurisdictions” (cities with populations over 50,000 and counties with populations exceeding 200,000). The remaining funds go to states for allocation to less populous towns and counties. HUD uses one of two formulas to determine each entitlement jurisdiction’s allocation, both of which are weighted to account for the share of the population living in poverty.

In FY 2024, the CDBG program provided $3.3 billion in grant funding to entitlement jurisdictions and state sub-grantees. Program regulations require at least 70 percent of CDBG funds to be used by local jurisdictions for activities that benefit individuals with incomes below 80 percent of AMI; the remainder can be used for emergency response or to prevent or eliminate slums and blight. In recent years, Congress has also made special CDBG appropriations to aid cities, towns, counties, and states responding to disasters.

National Housing Trust Fund

The National Housing Trust Fund is a HUD-administered block grant program designed to serve very low-income and extremely low-income households, including families experiencing homelessness. Funds are allocated to a designated state agency (typically the housing finance authority or state department of housing) using a formula that accounts for housing needs among eligible income groups. Awards are intended primarily for use in supporting the creation, rehabilitation, preservation, or operation of rental housing for the lowest-income households. The state agencies then determine which projects to fund. All assisted units must remain affordable for at least 30 years. Since 2017, more than 7,000 rental units have been built under the Housing Trust Fund.

The Housing Trust Fund differs from most other HUD programs in that funding is provided on a dedicated basis, rather than through congressional appropriations. Specifically, it is funded with a portion of a 4.2 basis point assessment on the new business generated by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two largest government-sponsored enterprises. Of this assessment, 65 percent is allocated to the Housing Trust Fund, while the remaining 35 percent goes to the Capital Magnet Fund. In 2023, the Housing Trust Fund received an allocation of $354 million.

Capital Magnet Fund

The Capital Magnet Fund is a competitive grant program administered by the Treasury Department. Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) and qualified nonprofit housing organizations are eligible to compete for program funds. These funds may be used to finance housing for low- and moderate-income households (at least 70 percent of a grantee’s award) and for related economic development and community service facilities. As of 2024, the Capital Magnet Fund has created more than 7,400 affordable homeowner units and 55,600 affordable rental units. Every dollar from the Capital Magnet Fund must leverage at least $10 in private and other public funds. Eligible uses include the creation of revolving loan funds, risk-sharing loans, loan guarantees, and other initiatives that can be used to attract private capital to economically distressed and underserved cities, towns, and counties.

The Capital Magnet Fund is funded with a portion of a 4.2 basis point assessment on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s new business, although it may also be funded by congressional appropriations (the Capital Magnet Fund receives 35 percent of the assessment on the enterprises, and 65 percent goes to the national Housing Trust Fund). In FY 2023, $321.2 million was awarded to 52 organizations, following a competition that saw 144 applicants request more than $1 billion.

Other programs

While this page covers the primary funding sources for affordable housing, other programs play an important role in local housing efforts or support unstably housed people. For example, safety net programs such as Medicaid and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families can be used for supportive housing and emergency housing assistance, respectively. Other programs listed below may also be leveraged for affordable housing, depending on the specific circumstances or objectives of a jurisdiction.

Rural Housing Service programs

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s Rural Housing Service offers single-family and multifamily housing programs to support a variety of activities in rural areas. Single-family programs help low- and moderate-income residents of rural cities, towns, and counties purchase homes and make home repairs, while multifamily programs provide support for acquisition-rehab and new construction, provision of related facilities and infrastructure, and project-based rental assistance. In FY 2023, the Rural Housing Service provided over $1.5 billion in assistance to 228,000 rural renters and committed $10.6 billion in loans, loan guarantees, and grants. More information is available on the USDA’s Rural Housing Service website.

Opportunity Zones

The Opportunity Zones tax incentive, created by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, was designed to spur investment in nearly 9,000 economically distressed census tracts. The program provides several types of tax incentives that reduce or defer the amount of taxes investors must pay for their capital gains. Opportunity Funds provide investors the chance to put that money to work rebuilding low- to moderate-income communities through pooled investments. The fund model is intended to enable a broad array of investors to pool their resources and increase the scale of investments going to underserved areas. However, research has shown that investors primarily target the high-end real estate market and that opportunity zones have not benefited low-income households or neighborhoods.